I wrote the following post-mortem on Dragon Age Legends during the summer of 2011, a few months after release. Because the game was still live at the time, the piece was never published. However, as the game has now been offline for over a year, and most of the development team has moved on from EA, I feel comfortable posting my thoughts from that time period.

My thinking today is different from back then. I have largely soured on the potential of free-to-play gaming as it almost inevitably leads to an unhealthy addiction to whales – customers willing to pay thousands of dollars for various items and perks. Legends never attracted the whales necessary to sustain itself, which is perhaps for the best anyway as I’m not sure how I feel ethically about players spending that much money on my games. (Having said that, I also feel one of Legends main problems was that we priced some items, such as energy, far too high.)

I do still believe in the potential of asynchronous gaming, especially for limited-scale, turn-based games (like Hero Academy or Ascension) or for long-term, real-time games (like Neptune’s Pride or Civ4’s PitBoss mode). With Legends, however, the asynchronous format screwed up an otherwise solid gameplay loop – the energy system artificially limited game flow and tying the game’s mechanics to real-world time made balancing for every type of player a nightmare.

These novel formats – appointment mechanics, friend recruitment, limited session lengths – seemed interesting at the time, but I now believe what should have been obvious – that a game’s format should enable and support the game experience, not limit and complicate it. Looking at the core gameplay systems now, I can’t help wonder how the game would play if remade with a dynamic XCOM-style campaign, with each turn-based battle moving the game clock forward, which would then determine how fast the characters heal and consumables are crafted. The game loop would still work and all the energy gate, friend list, and free-to-play complications could just be dropped. Maybe someday…

Our primary goal with Dragon Age Legends was to create a “social game for gamers.” This social RPG combined the interesting decisions and difficult trade-offs found in traditional games with the innovations of the social game world. In fact, the game is split into two halves – a turn-based tactical combat system similar to Japanese RPGs like Final Fantasy and a persistent, appointment-based castle-building game inspired by asynchronous Facebook games like FrontierVille.

What Went Right

1. Core Design Loop

We designed our core game loop specifically to match the Facebook format, with players jumping into the game for short play sessions throughout the day. The character’s core stats (health and mana) do not regenerate naturally as they do in most RPGs. (Health does replenish but only outside of combat and only in real-time – one heart per hour.) Thus, if players want to restore their health and mana between battles, they need to rely heavily on their consumable items – health and mana potions, injury kits, and mana salves.

These consumables are the fuel that powers players though combat. What makes Legends unique compared with traditional RPGs is that the player is actually in control of the supply of consumables as the player can create them in the castle with timed appointments. (For example, the castle’s apothecary can create two health potions in 30 minutes.) If a player begins running low on a certain item, she can always invest extra time at the castle to rebuild her supply.

The two halves of the game – the castle and the combat – create a self-sustaining economic loop. Gold earned from fighting battles and completing quests can be invested in expanding the castle and upgrading its rooms. Accordingly, the castle creates the potions, salves, and bombs that the player needs to defeat the increasingly difficult monsters encountered over the course of the game.

Hence, the combat and the castle provide context for each other, motivating the player to keep fighting and to keep building. This loop gave the team a clear central vision for the game, to pair the meaningful decisions of a turn-based RPG with the compelling persistence of a castle-building game. The system proved a good fit for Facebook, in which players might dip in at any time to fight a couple battles or just to craft a few more potions.

2. Meaningful Social Hook

We also wanted our game to have a meaningful social hook – a reason to be on Facebook instead of just being on the Web, like the game’s predecessor, Dragon Age Journeys. Simply put, friends should make the game more fun.

Further, we were not impressed with how many Facebook games implemented social features, often forcing players to pay a “friend tax” by, for example, asking 10 friends to help finish a building. These features help social games spread virally, but they often feel artificial and even abusive of the player’s social network.

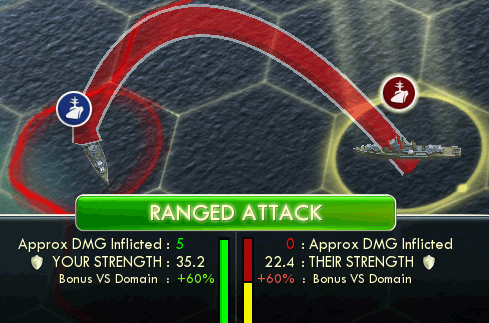

Instead, friends should be a part of the core gameplay, so that players will naturally want to invite their friends to join. As a party-based RPG meant to be played a few minutes at a time in a browser, we had an opportunity to address this problem with a new format – the asynchronous MMO. Although players develop a single character, they recruit their friends’ characters asynchronously to help complete the party in combat.

The details of this feature led to some interesting social dynamics. A recruited hero receives a gold bonus that the hero’s owner can pick up the next time he logs on. As players tend to recruit higher-level and better-equipped heroes, their owners have a strong incentive to keep improving their characters, so that they will earn more friend gold.

Recruited heroes enter a rest state after each use, from a few hours to most of a day, depending on how much damage they withstand in combat. Thus, deciding which friend to use and for.which battle is a strategic choice as one’s most powerful friends can only be used a few times each day. In other words, friends become an important, but limited, resource.

This system led to much interesting discussion between our players about how friends should develop their heroes and even whether one friend was using another friend’s character reciprocally enough. In other words, the social interactions between players had become meaningful. As a nice side benefit, Legends differentiated itself from other RPGs because players were regularly exposed to the entire skill tree via their friends’ characters.

3. An Actual Closed Beta

The term “Beta” has lost some meaning over the years as almost every Web-based game exists in a state of perpetual Beta. FarmVille, for example, didn’t remove the Beta tag until April of 2011, 22 months after the initial release and well after falling from its peak of 83 million monthly active users in March 2010 to today’s 43 million.

Many Facebook games are developed iteratively in public, starting from a minimal initial version with many missing features. This approach has many benefits as teams get immediate feedback about what is working and what isn’t – a big improvement from the multi-year silos of traditional game development. However, there are disadvantages to a continuous public development process; early design decisions can become permanent as backing away from them might upset the current community.

We took a different approach as we started our public development with a Closed Beta from January 2011 to our release in mid-March. Just like a traditional MMO, we encouraged players to sign-up for the Beta online and then periodically sent out keys to grow our player base, letting in over 50,000 players.

During this period, we conducted a database wipe every two weeks, both for the sake of lowering our engineering overhead as well as helping to focus attention on the early game by funneling players through it repeatedly. Because our players understood that their characters and castles were not permanent, we were able to experiment and make rapid changes in ways not possible during an Open Beta.

For example, during the Closed Beta, we added a strict inventory cap, removed Always Critical Hit items, slowed the leveling curve, rebuilt the first five maps, and reworked the skills system multiple times. Although these changes were not always popular, any negative impact was lessened by the known lack of persistence.

In fact, we even began charging real money for our premium currency (Crowns) during the Closed Beta, mostly to make sure the system worked. Surprisingly, players began spending large sums of money, even with the knowledge that their characters would soon be erased. We quickly developed a system to return all spent Crowns to players after each database wipe to give spenders more confidence in their purchases. This simple change was worth the effort as the information we gained was invaluable to our monetization strategy.

What Went Wrong

1. Client/Server Synchronization

We devoted the first few months of the project to rapidly prototyping the combat system. which went quickly because we reused code, art, and animation from EA2D’s previous Flash-based RPG, Dragon Age Journeys. This period of quick-and-dirty development led to important innovations, such as the accessible, icon-based health/mana system and the extra combat step for consumable use.

However, Journeys is a more straightforward game that runs entirely in the player’s browser, unlike Legends, which requires a client-server architecture. When building the prototype, we ignored this difference for the sake of development speed, which cost us in the long run. Because of concerns over player cheating, we couldn’t just allow the client to handle the combat, and because of lag issues, we couldn’t let the server handle it. Thus, the combat calculations needed to run in parallel on both the server and the client, which meant we had to ensure that the two sets of algorithms were identical.

When the time came to turn on the servers for real testing, the client kept falling out of sync with the server because we had no real solution for guaranteeing the calculations would be in lockstep. For a time, we considered some technical solutions that would allow us to write the code in one language which could be run (or recompiled to run) in both places, possibilities which included the Google Web Toolkit, the haXe language, and running Javascript on the server.

In the end, we adopted the simple, but painful, solution of using manual brute force to ensure that every combat function was written identically in both Java and ActionScript. This process cost months of time for our lead gameplay programmer, during which time design and testing was essentially paused because the combat system no longer worked. This ugly solution blew a gaping hole in our schedule as little design or testing could be done.

2. Brittle Quest System

One big advantage of developing games on the Web is that they can be constantly updated – multiple times a day, if necessary. Bugs get fixed faster, and no gatekeeper stands between the developer and the player, slowing down the delivery of content. This rapid pace, however, does have its downsides, one of which is the challenge of keeping the persistent data of hundreds of thousands of characters in a playable state after every update.

Unfortunately, our quest system commonly dropped a small, but significant, number of players into a broken state after game updates. The problem was that the system did not fail gracefully. If a player was in the middle of a certain event that got changed, renamed, or even removed during an update, she may suddenly have no way to finish her current quest.

This problem was compounded by the strict linearity of the map and quest design. Maps were often a linear series of nodes that were paired with a linear set of quests that a player could only progress through in a certain, set order. If these nodes or quests were modified in any way, then players in an intermediate state could easily fall off the quest chain, with no hope of recovery. They might play through the rest of the game without ever seeing another quest!

As these issues began appearing, our engineers scoured the database, looking for characters with broken quest states, and then manually repaired the data. Eventually, we developed a tool to assist with this labor-intensive process as well as safeguards within the code to automatically fix stuck characters, if possible. Nonetheless, we lost significant engineering time during a key part of the project. The lesson learned is to design game content and systems that are flexible enough to fail gracefully when change inevitably occurs.

3. A Fear of Social

Our goal was to make a social game for gamers, many of whom express grave reservations about the tactics used by typical Facebook games to spread virally, by spamming friends with requests and notifications to pull them into the game. We put our greatest effort into making an engaging RPG and only developed social features that treated our players’ social capital with respect.

Thus, although we developed what we believed to be a fun, core MMO that fit the asynchronous format of the Web, our game was light on the viral loops found in most social games. Although Legends attracted a committed audience eager for new features and more content, our viral factor was very low; our players were neither inviting their friends into the game nor convincing lapsed veterans to return.

The majority of our team, including all of our designers, had never made a social game before, which meant that we were simply not familiar enough with the social hooks and viral features Facebook provided us. The list of standard features that we did not have at launch speaks to our naivety about what makes social games work and spread:

- No use of Facebook’s notification/request channel

- No rewards for clicking on another player’s wall posts

- No collaborative tasks or reasons to ask friends for help

- No gifting between players (even of actual loot items, as is common in MMOs)

- No daily bonus for returning to the game

Further, we lacked many of the tools common to social game developers, such as A/B testing and a metrics viewer customized for our game. Instead, we had to rely on our own intuition and feedback drifting in from our community, which meant that we were never quite sure why our basic numbers (DAUs, MAUs, ARPU, K-factor, etc.) were either going up or going down. Ultimately, we were not developing a game that played to the strengths of its platform.

When the game was taken offline in June 2012, the team released a free standalone version that dropped the energy system and allowed people to either start from scratch or import their online characters. The game balance is not quite right as the Legends was not built to be played in long, offline sessions. For example, friend cooldowns were removed but not replaced by anything else, so the player can simply recruit the best allies for every battle, which was supposed to be a core gameplay decision. Further, the crafting system is still in real-time, which goes far too slow if the game is not played in bursts. Still, the game is at least available, which is better than many other Web games which just vanish into the ether.