Settlers of Catan

Settlers is in an odd place nowadays. It was the game that first broke German-style gaming in America, and it has been successful enough to reach a certain level of critical mass. I have even began seeing Catan at the houses of friends who normally would only have Monopoly and Scrabble in their game closets and have certainly never heard of the term “German” gaming. Nonetheless, Settlers has a surprisingly low BGG ranking, and I have the sense that much of the hard-core crowd has moved on from Settlers to more complex games like Puerto Rico and Caylus. It may now be a victim of its own success, which is a shame because Settlers of Catan is a brilliant, brilliant game, superior to all but a handful of games on this list. Three elements of the design stick out in my mind. First, the pure simplicity of the mechanics, which almost anyone can grasp within a few minutes. No hidden modifiers exist that need to be remembered, and almost all the rules are spelled out on the board and cards in an intuitive way. Second, the embrace of randomness, both for the map layout and during the game itself. Having a random map greatly extends replayability, and random resource generation nicely avoids the “perfect information” problem from which many Germany games suffer. Finally, trading has always been a rich game mechanic, and Settlers is built for trading. Isolationists will almost never win, making Settlers one of the most socially interactive German games. No game collection should be without it.

Grade: A (BGG: 7.73)

Carcassonne

The joy of playing Carcassonne is not altogether different from the joy of finishing a puzzle. Finding the perfect spot for your piece is a great game mechanic, not to mention an accessible one. However, Carcassonne does not have intuitive scoring rules. The danger is not the complexity – it’s that the game looks simpler than it actually is, which inevitably leads to a disappointing experience when a new player trips over the tricky farmer rules. Another game for every collection, but I wish the designers had pushed themselves harder to keep the scoring simpler.

Grade: B+ (BGG: 7.57)

Caylus

The last game of Caylus I played was six hours long, which was about five too many. Caylus is the worst example of a trend in German games to minimize hidden information and random elements. These traits are valued highly among the most hard-core of board gamers – the ones who would like to win 10 games out of 10 versus newbies based on their own superior skill. Unsurprisingly, Caylus is a popular game among this crowd. To me, it feels like slow-motion arm wrestling. Between two players, that dynamic is actually not so bad. Among bigger group, it’s a pretty painful slog.

Grade: C (BGG: 8.09)

Bang!

Bang! is a blast! Essentially a souped-up version of the old college dorm ice-breaker, Mafia, the game revolves around hidden identities. Play sessions tend to be lively and memorable – I’m still smarting from the game I came an inch away from winning as a Renegade by convincing the Sheriff I was the Deputy until I got killed by the Dynamite! Aaargh! As a deeply asymmetrical game, the balance is a little dubious, but Bang! certainly proves that pure fun is more important!

Grade: B+! (BGG: 6.92)

Bohnanza

If Settlers is a trading game, then Bohnanza is a trading game on steroids. Every rule in the game exists for the sole purpose of encouraging trading, and they work perfectly. So perfectly, in fact, that the rulebook has to specify that it is ok to refuse gifts! (Imagine needing a rule like this in Settlers…) The only downside to Bohnanza is that there is so much trading that there is an unfortunate potential for hurt feelings with regards to who trades the most with whom. If your game group is sensitive to these types of problems, the game may not be right for you.

Grade: B (BGG: 7.25)

Citadels

Quite a few games have the mechanic of I-know-that-you-want-to-choose-X, but since you-know-that-I-know-that-you-want-to-choose-X-you-won’t-choose-X, but as you-know-that-I-know-that-you-won’t-choose-X-then-maybe-you-will-choose-X-after-all, and so on. Citadels, however, is built entirely around this tension, via the secret selection of roles at the beginning of each turn. Of course, the tortured logic train never leads to a definite answer, so the guesses have to be based on pure personality, making Citadels a great game to be played among old friends. Who is the greediest? The sneakiest? The most aggressive? The most conservative? Well, it’s a lot more fun than the Myers-Brigg.

Grade: A- (BGG: 7.37)

Pandemic

Jonathan Blow, designer of Braid, gave an interesting talk this summer on the common disconnect between narrative and gameplay in video games. A good example is the choice made in Bioshock between harvesting and rescuing Little Sisters. The narrative tells the player that the choice matters, but gameplay tells the player it doesn’t matter. Board games also have a similar problem when the theme does not match the mechanics. Although theme can often be a secondary concern for board games – consider how similar the gameplay is between San Juan and Race for the Galaxy yet how completely different the setting is – the best games often find a way to pair the two. Pandemic is one such game. The players are disease specialists who work closely together to control outbreaks across the globe. More importantly, the players feel like they are racing to find creative, cooperative solutions to a challenge where the deck is literally stacked against them. (The innovative deck re-shuffling mechanic, in which previously drawn cards are placed on top, is especially worthy of note.) This pairing contrasts with another fun cooperative game, Shadows over Camelot, in which players are supposed to be Knights of the Round Table, but they feel more like they are playing whack-a-mole by assembling the best poker hands. The pairing of mechanics and theme is what makes Shadows just a good game and Pandemic a great one.

Grade: A (BGG: 7.92)

Ticket to Ride

I have written before on the bizarre “backstory” behind Ticket to Ride. Fortunately, the game itself is excellent. Further, Ticket to Ride is extremely easy to teach and also moves at a brisk pace, making an ideal introduction into the larger board gaming world for new players. Ticket to Ride is also at the vanguard of a trend which I believe will become increasingly dominant in the near future, what I will term “competitive solitaire”. The goal of the game is to build a network of tracks which connects a random selection of cities. Other players can occasionally affect your plans by grabbing a route you need, but overall, the feeling of the game is of trying to make as many of your own connections work as possible, not of trying to screw over your opponent. The big advantage of competitive solitaire is that when a player loses, they tend to blame their own play instead of their opponents’ decisions, which usually encourages players to try again to “get it right” the next time.

Grade: A- (BGG: 7.62)

Puerto Rico

The reigning BGG champion, Puerto Rico definitely sums up what is great and not so great about German gaming. Plenty of interesting strategic decisions combined with elegant mechanics – such as simply adding a gold coin every turn to unselected roles as a reward – earn the game much respect. However, the lack of hidden information and (almost) no random elements make the game difficult to enjoy when playing with optimizers, who tend to be the ones most drawn to deep board games in the first place. To paraphrase Groucho Marx, I don’t want to play Puerto Rico with anyone else who wants to play Puerto Rico.

Grade: C+ (BGG: 8.38)

Race for the Galaxy

Inspired by Puerto Rico (not to mention San Juan), the card game Race for the Galaxy centers on building up a collection of planets and developments for points or for production, which can later be converted to points via trade. The big difference between Race and Puerto Rico is that the players’ build options are hidden in their hands and that the action phases are played simultaneously. These distinctions make Race significantly more accessible because player have to make intuitive guesses, instead of over-analyzing the set turn order and complete information of Puerto Rico. Games of Race can be played very quickly, probably having the most interesting decisions per minute of any game, ever. Like Ticket to Ride, Race could also be described as competitive solitaire, which makes the game – despite its complexity – relatively accessible.

Grade: A (BGG: 8.05)

Set

Why do people walk tightropes? Why do they skydive? Why do they run marathons? For the same reason the play Set – to test their limits. More of a time-sensitive puzzle than a game, Set is not to be undertaken lightly. The challenge is to find specific three-card patterns before your opponents can, and the experience is nerve-racking. Many people will hate Set because the game can literally give you a headache, but if you want to push your brain as hard as you can, Set is the game for you.

Grade: B- (BGG: 6.53)

Lost Cities

One of the biggest advantages physical games have over digital games is that all one needs to become a game designer is a stack of cards, some stickers, a few markers, and maybe a die or two. In some cases, just a single deck will do. Lost Cities bears the obvious marks of deriving directly from a standard pack of playing cards. The game has five “suits”, with cards ranked from 2 to 10 and three face cards, er, I mean, investment cards. The gameplay itself uses a classic risk/reward mechanic that encourages multiple, early investments but penalizes players who cannot complete all their goals. The discard mechanic is interesting as well, putting game length squarely under player control. My only wish is that designer Reiner Knizia had pushed himself a little harder to simplify the scoring rules as they don’t match the simplicity of the rest of the game.

Grade: B (BGG: 7.34)

Mamma Mia!

An interesting memory game, Mamma Mia! is also nearly impossible to explain to players in words. Players submit pizza ingredients and orders into a collective stack, hoping that when the stack is replayed, the ingredients will match their orders to score points. The trick, however, is that ingredients are communal – if you remember that I submitted a bunch of mushrooms earlier, you can steal them for your own mushroom pizza order if you submit it before me. One game in, however, and most players are hooked. Most importantly, Mamma Mia! does an excellent job of keeping the amount a player needs to remember in that sweet spot between trivially easy and hopelessly difficult.

Grade: B+ (BGG: 6.62)

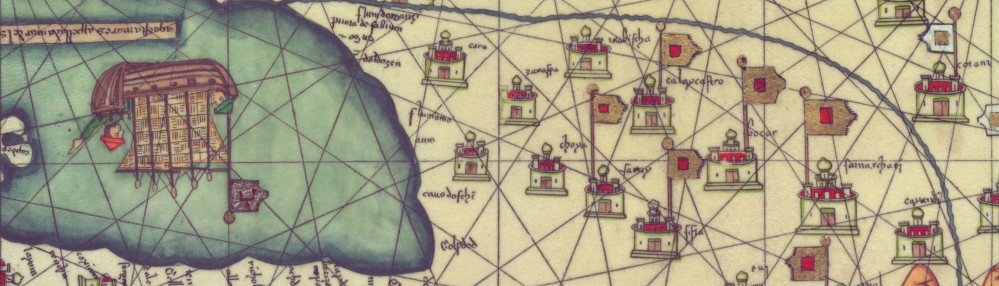

Age of Renaissance

Some games simply have gone a rule system too far. Ostensibly a sequel to the old classic Civilization, Age of Renaissance has an absolutely gorgeous map of Medieval Europe as well as a promising trade model which encourages monopolizing resources spread across the whole world. Nonetheless, the game is virtually unplayable because of the cumbersome technology system, encompassing 26 techs, all of which can be learned in a single game and each of which changes how the game plays for the owner. Keeping track of all those bonuses and special rules would be fairly trivial for a computer, but the experience is a slog for a human. Only cutting technologies (or, at least, taking away their unique bonuses) from Age of Renaissance could have saved this frustrating, yet enticing, game.

Grade: C (BGG: 7.17)

History of the World

As I discussed with Pandemic, theme is a tricky problem – especially as many board games can easily be converted from one theme to another without damaging the core play experience. Further, quite a few games that try to differentiate themselves on theme often do not actually deliver on that promise. How many world history games devolve into rich-get-richer scenarios which bear no resemblance to actual world events. (Indeed, I’m guilty as charged too! The Civ community calls this the Eternal China Syndrome.) History of the World is not one of these games. The designers solved this problem by building the fall of empires into the core gameplay – and not as some obscure option that players would learn to avoid. Each turn in HotW, players are forced to leave their old civilization behind and start a new one. The audacity with which the designers violated such a basic assumption – that players get to build off of their gains – is remarkable. That in doing so they built a game which looks like real world history and is also fun to play is an astonishing achievement. The scoring mechanism itself, which increases the total points available each turn to keep all players in the running, is worthy of note too. The game may certainly be a little long for some, but I can think of few other games that deliver on their theme’s promise as well.

Grade: A+ (BGG: 7.17)

Taj Mahal

I fell in love with Taj Mahal right away. The rules are so simple, yet so rich for multiplayer competition – indeed, Taj Mahal is one of the most cutthroat games I have ever played. The central strategy is knowing exactly when to push for victories and when to hold back as the rules naturally prevent rich-get-richer situations. Further, the penalty for overreaching is severe, perhaps too severe for more casual gamers. Nonetheless, Taj Mahal is a fascinating game, with some nice random elements and a scoring system (similar to History of the World) which encourages comebacks by giving out more points in the latter turns.

Grade: A- (BGG: 7.67)