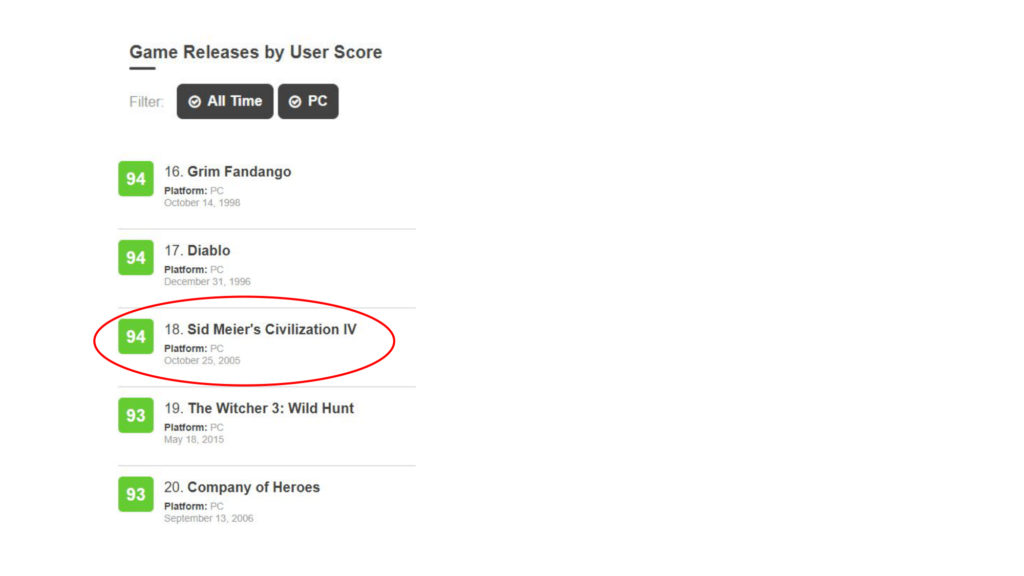

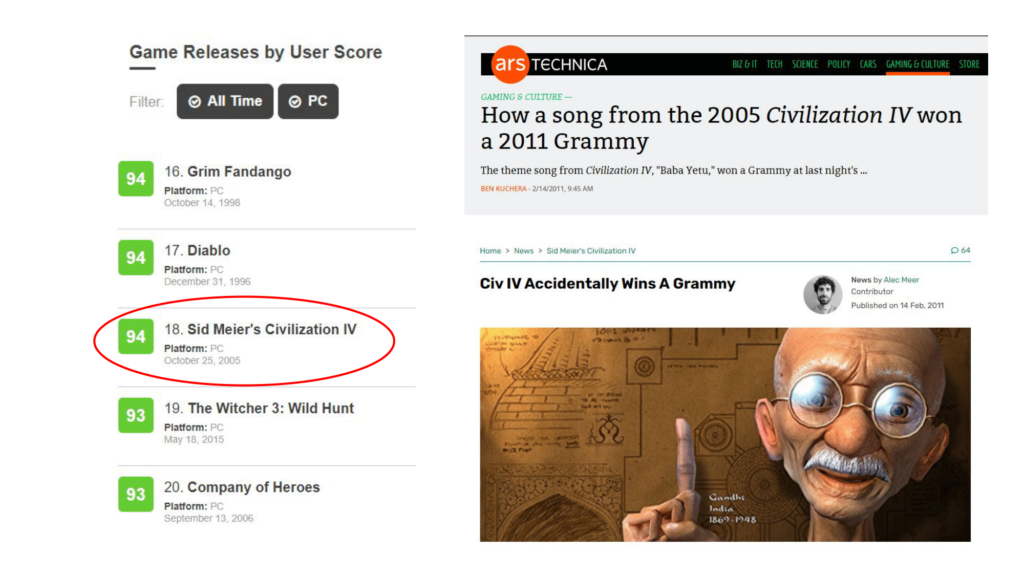

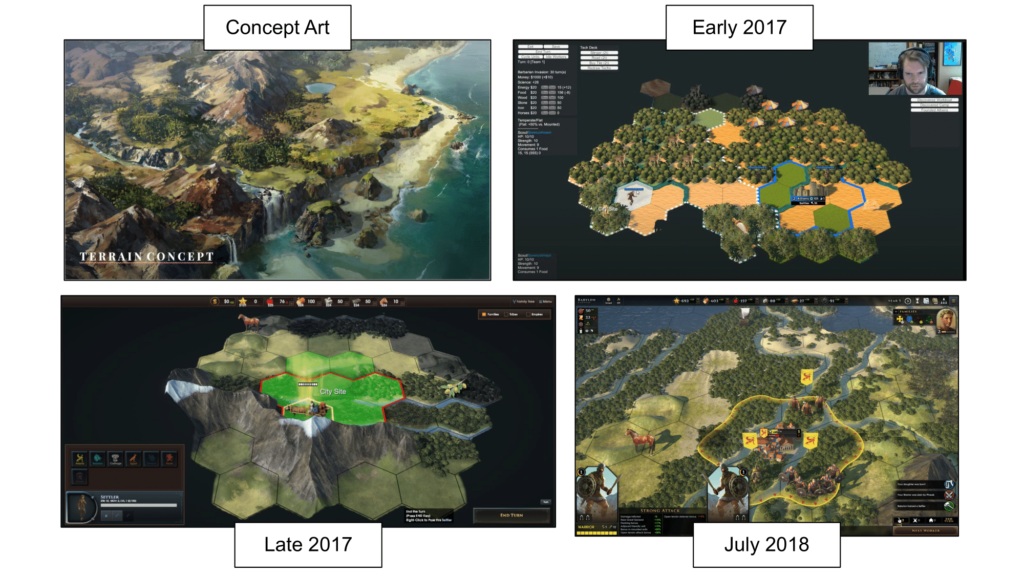

I gave an Old World postmortem at GDC 2022, which is available on YouTube:

However, I fully scripted the talk ahead of time, so I decided it would be worth taking the time to post the slides online, in three parts to have mercy on your browser.

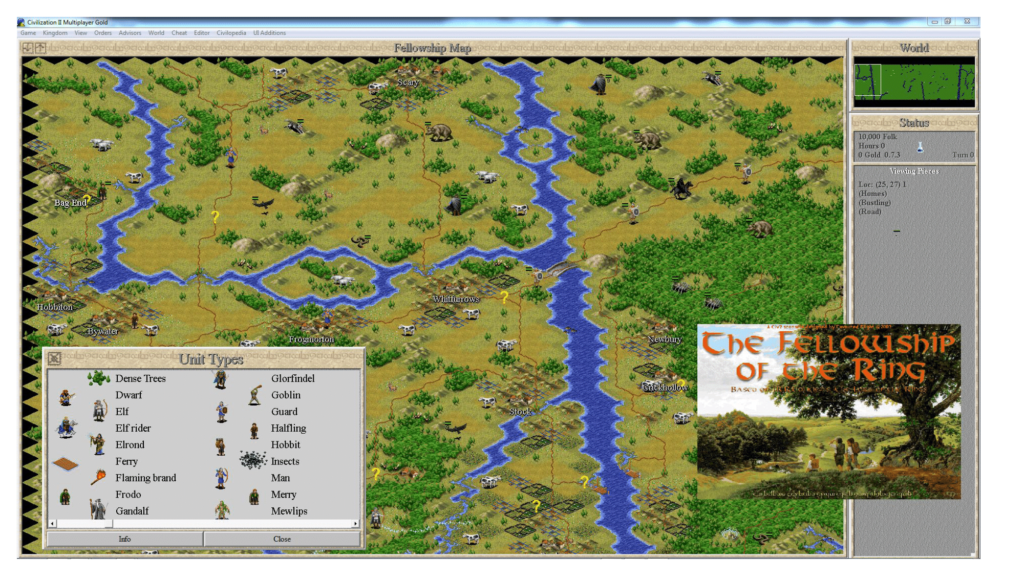

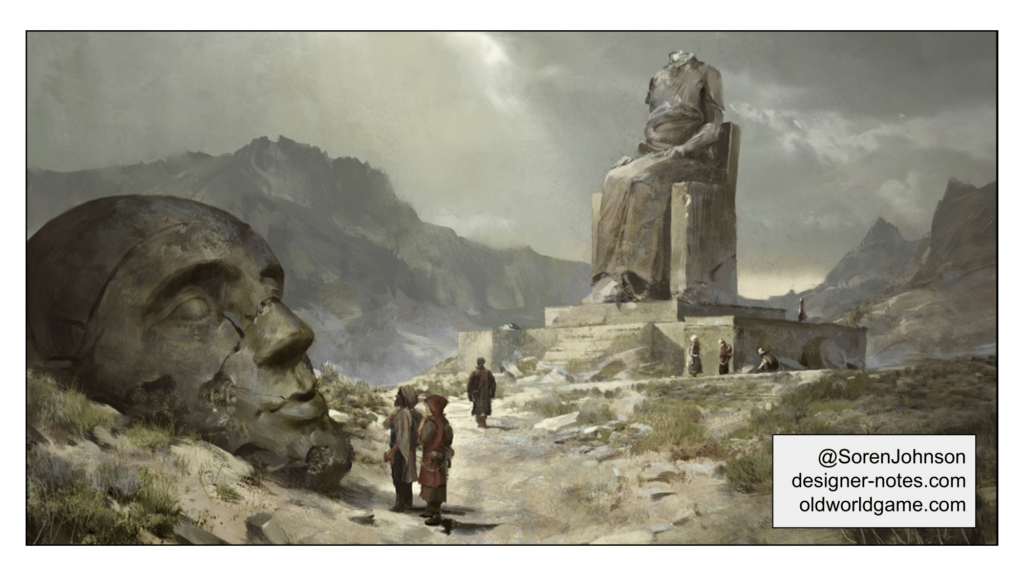

After shipping Civ 3, one thing I heard often from the Civ 2 community was that the modding tools lacked support for something called “events” which I eventually learned meant a system of triggers and effects that modders could use to give games a narrative arc. It could create a series of chapters, for example, which pushed the story forward when the player achieved certain milestones. I tried out a series of mods to see what was possible and was surprised to see how effectively people could push the Civ engine to create something completely new. For example, here is a Civ 2 Fellowship of the Ring mod which lets you retrace Frodo’s journey from the Shire to Moria, encountering all the events of the book along the way.

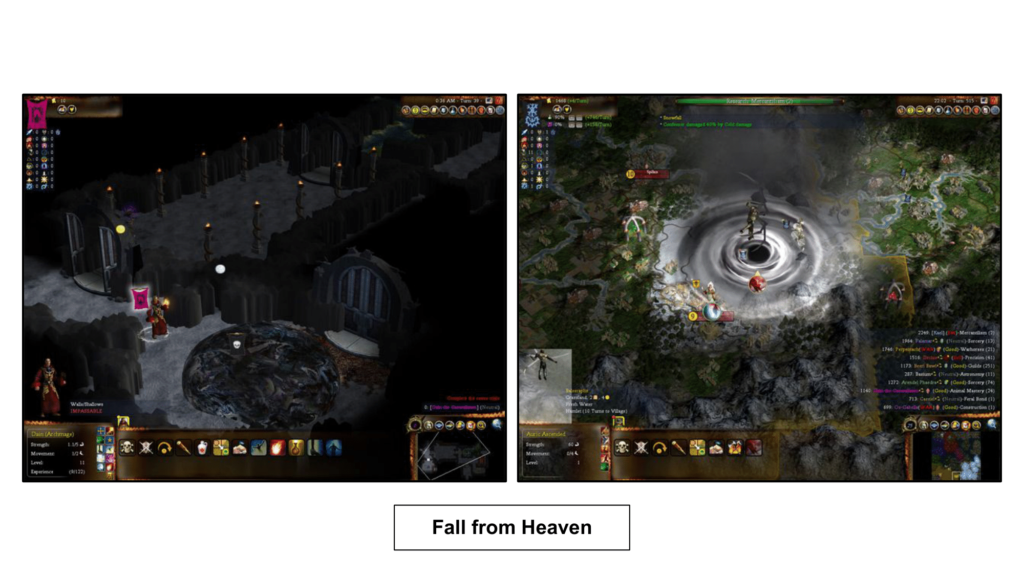

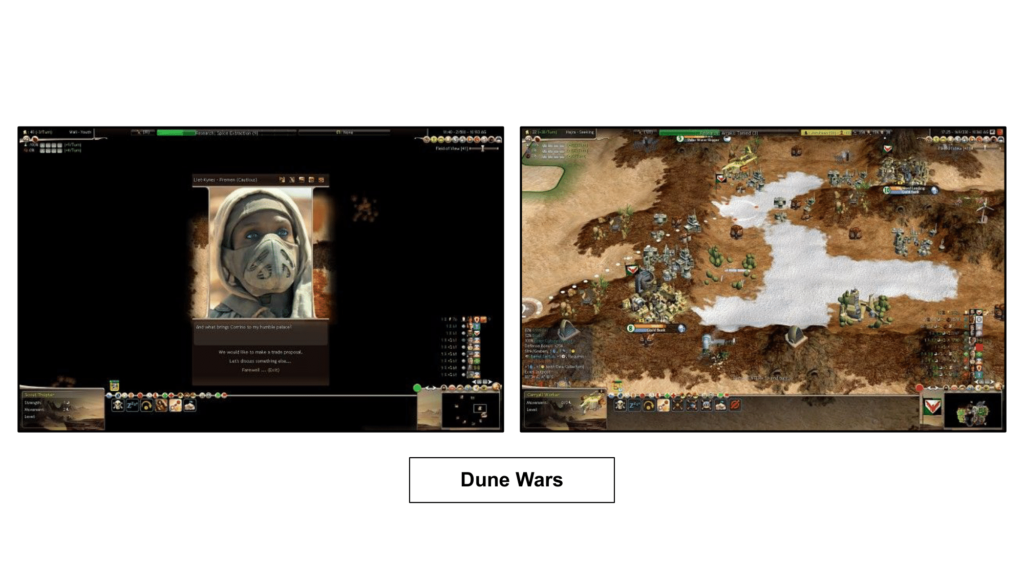

So, to enable this type of narrative-focused mod, we added triggers and effects to Civ4 using python as the scripting language and, ultimately, just released the game source code itself, which led to some amazing mods, like Fall from Heaven…

…and Dune Wars, both of which completely transformed the game and proved the amazing potential for both story and modding in 4X games. However, although I had given modders all the power they needed, I hadn’t actually done the work myself on how to make narrative work in a 4X game.

I noticed that events were starting to show up in various strategy games, with increasing depth and complexity. They added real texture to the experience and, perhaps more importantly, variety.

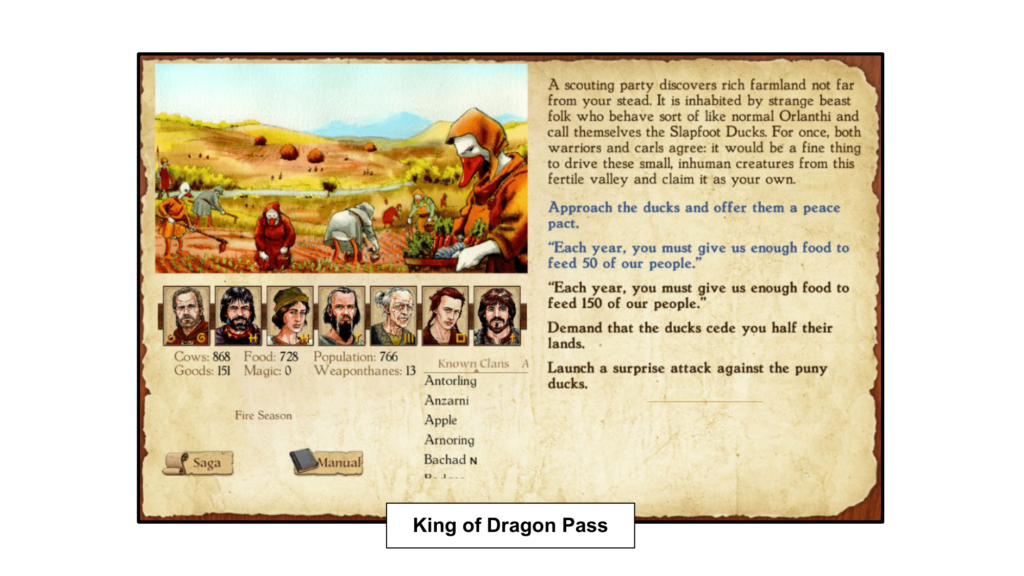

The most interesting mixture of strategy and events was the cult classic King of Dragon Pass, a 1999 game that vanished without a trace on release and then somehow snowballed into a hit decades later as word spread of its wild mix of traditional 4X strategy, clan management, and dynamic narrative. The event system was the star, and your choices largely determined the path your game took, often in wildly unpredictable ways. Each event forces you to make difficult tradeoffs between the demands of various factions, both internal and external to your tribe, just as we wanted to do with Old World.

However interesting this was, it’s not a game I could make. First of all, the game has an actual beginning, middle, and end, and I have neither the interest nor the ability to tell a single, cohesive story. More importantly, Dragon Pass doesn’t tell you the effects of your decisions, you are meant to just intuit the results, which works for some games but not for Old World, a game where transparency is one of the most important design aesthetics. The event system might surprise you, but the direct result of each of your decisions needs to be clear. For me, the promise of a strategy game is understanding what’s going to happen each time you click a button while still not being able to predict the future.

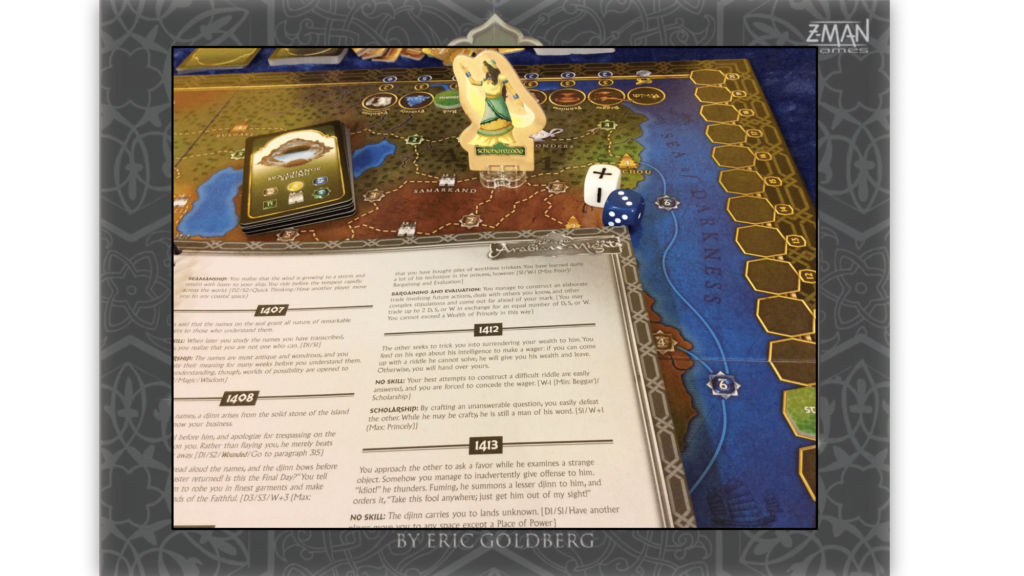

So, because transparency was important, I turned to the world of board games for inspiration. Specifically, the dynamic narrative masterpiece Tales of the Arabian Nights, which comes with a gamebook of over 2,000 events, randomly drawn from a deck of cards, and which both react to and can change the player’s current state. The mechanics for choosing events and how they affect the player are transparent and easy to understand, which was necessary because, as with all board games, the players have to do all the work themselves.

So, for example, having the Wit and Charm trait might help you escape a Vengeful Sorceress while an unlucky player without that trait might end up Ensorcelled, which will affect further events down the road. What inspired me about this system was that it was robust – it’s not an intricate event tree where missing a node might cause a story chain to break. Instead, the events are loosely coupled as they are meant to work together regardless of which random set you draw each time you play the game.

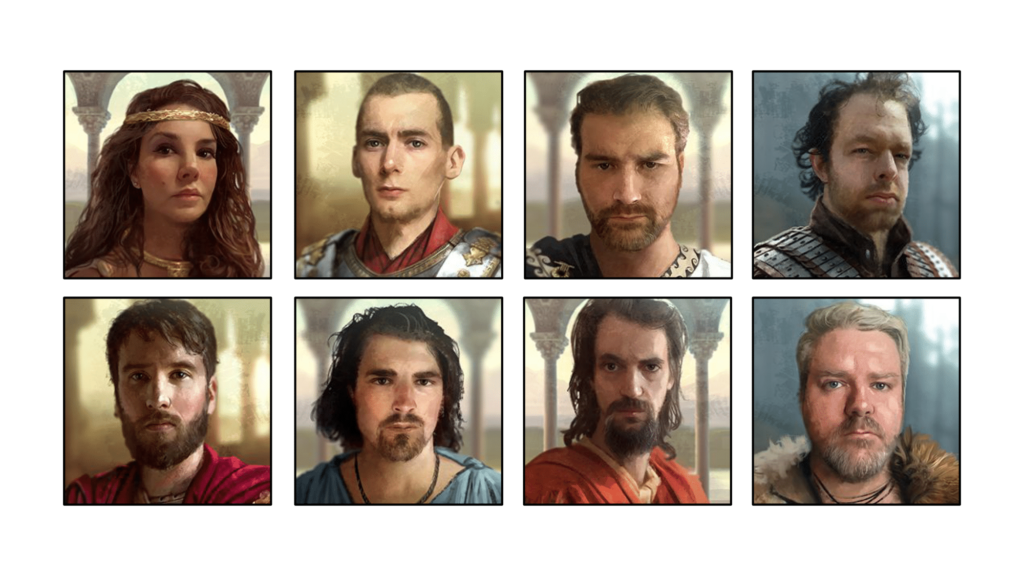

One of the benefits of a loosely coupled system is that multiple authors could create events at the same time, without requiring close collaboration or really even any collaboration. Here are some of the authors of the over 3,000 events currently in Old World, led by our CEO and Creative Director Leyla Johnson. Many of these writers worked on the project at completely different times, creating dynamic story arcs by accident. One writer might add an event that results in your Leader becoming a Drunk while another author, years later, creates an event that only triggers if the Leader is a Drunk, and now we have the makings of a little story. Indeed, as we add more events with each bi-weekly update, the story system becomes more and more cohesive as more events are added to cover all the unusual permutations that might happen for each playthrough.

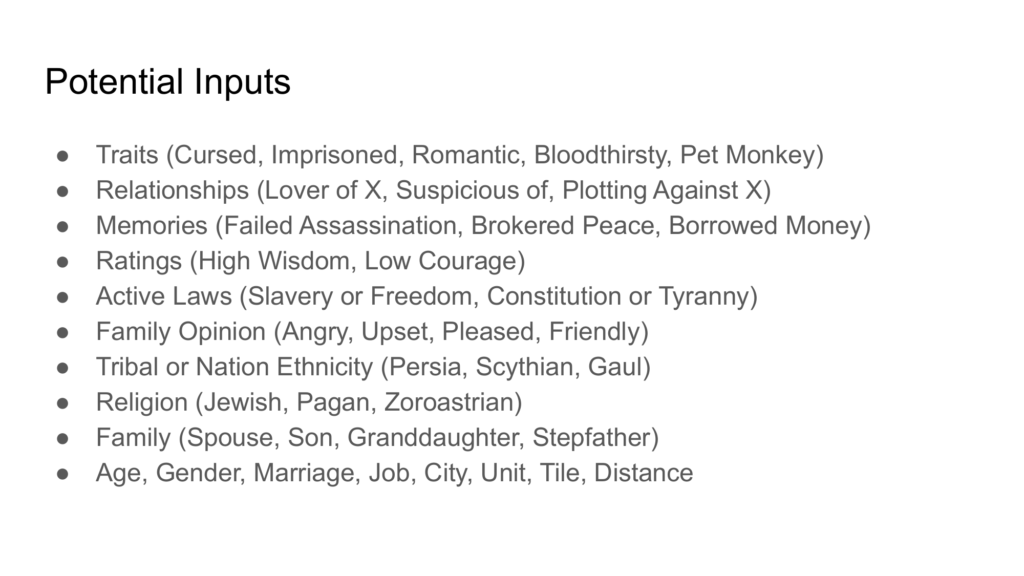

Here are just some of the possible inputs that the event system can look for and most of these can be changed by the system as well. So, the event system is a virtual deck of events where each one has a potential trigger (such as meeting a new nation), a set of requirements (like a childless leader), and possible effects (like a foreign spouse). It’s a broad, deep system that makes one look forward to each new turn to see what will happen next.

What I might be proudest of is that the multiplayer community for Old World plays with events turned ON – we had assumed that players who wanted to play competitively with each other would be put off by the randomness of the system, but they feel like the game is not complete without it. In fact, we put a lot of work into maintaining an alternate version of the game without events or characters or families or all the things that increase randomness, but I’m glad to say that it was probably a waste of time.

One of the best thing about the event system is that it adds content to the game without bloating the design, without adding new rules for the players to learn. We currently have over 3,000 events, but doubling or tripling that number will only add variety to the game without adding any more complexity. Often, with strategy games, less is more, but this is one place where more is actually more. It’s the same reason why card-based wargames like Twilight Struggle and We the People have become popular – it creates a deeper experience while keeping a slimmer ruleset.

Ultimately, the event system ensures that no two games play out the same way as there are endless possible stories as one event leads into another, changing the path of your game while your in-game choices feed back into the event system itself. I accidentally built a interactive fiction engine inside of a 4X game, and I am very excited to see where our writers – and the modding community – can take it.

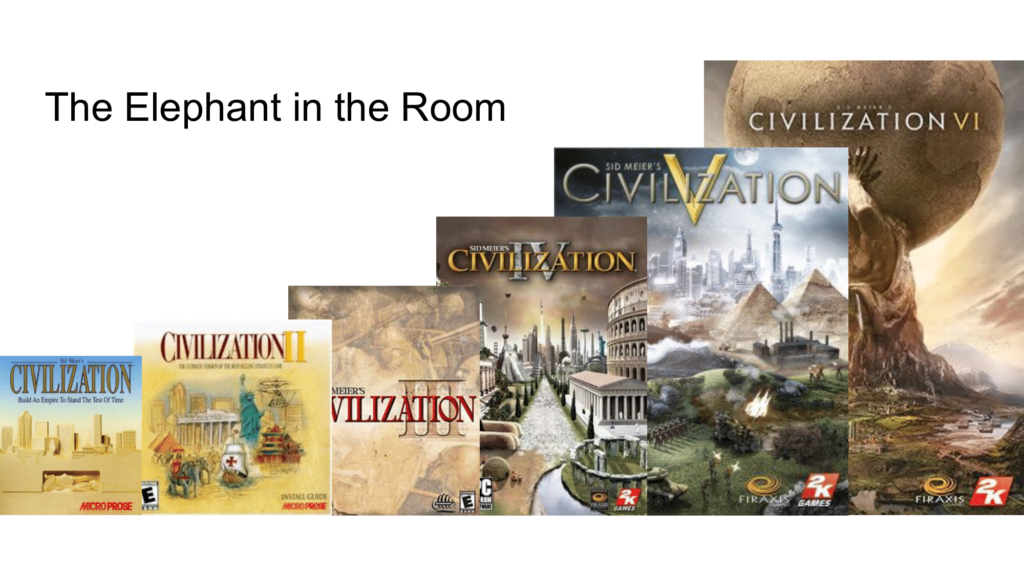

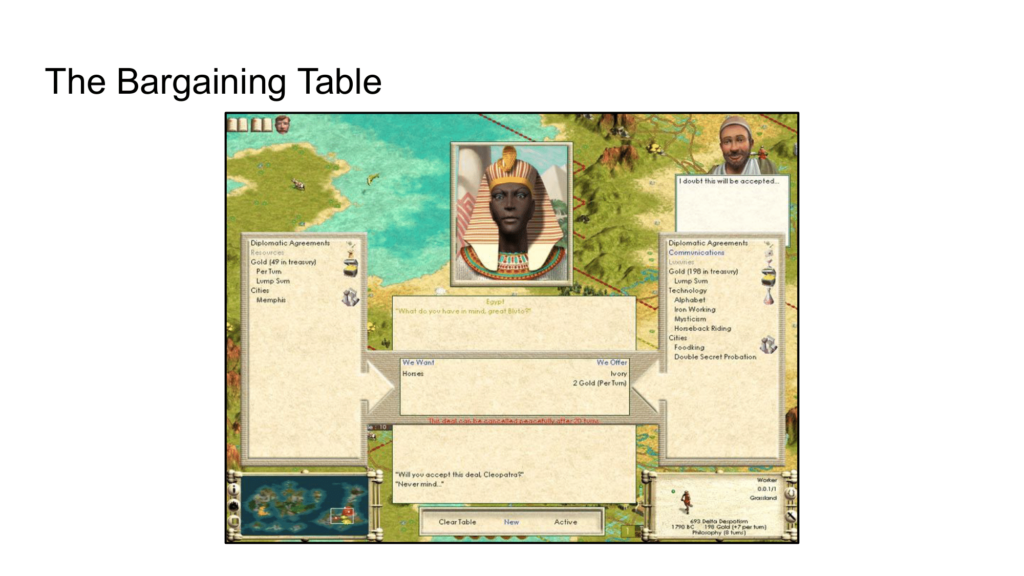

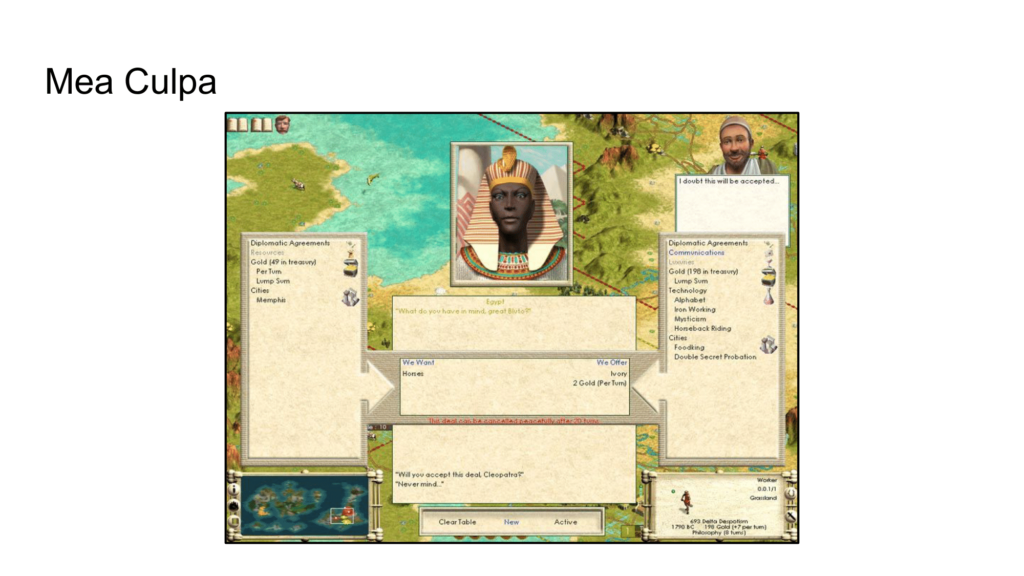

In Civ 3, we introduced the bargaining table to the 4X genre, pick and choose what you want to give and to receive from all sorts of potential options. It’s become a staple of the genre.

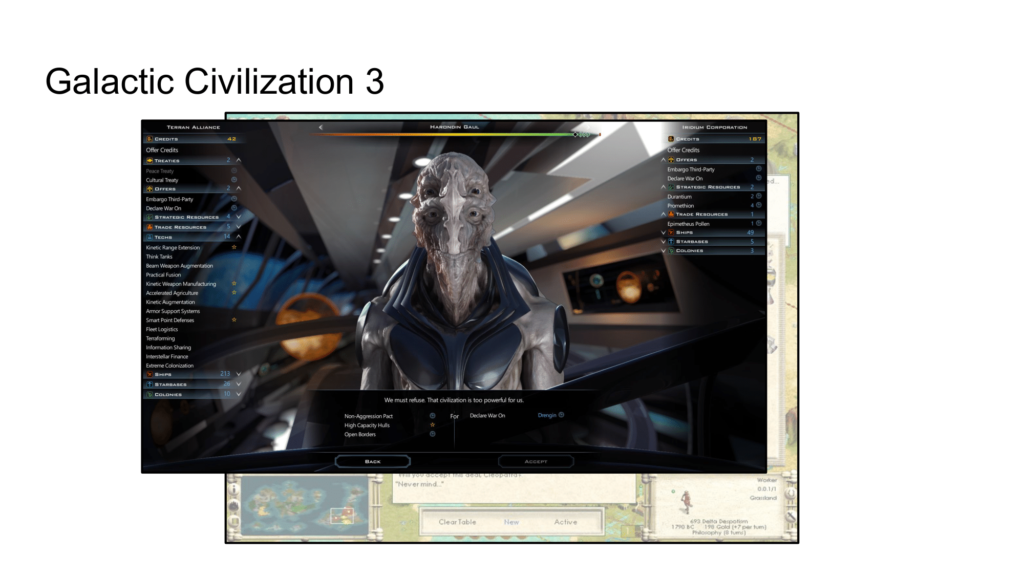

Here it is in Galactic Civilization 3.

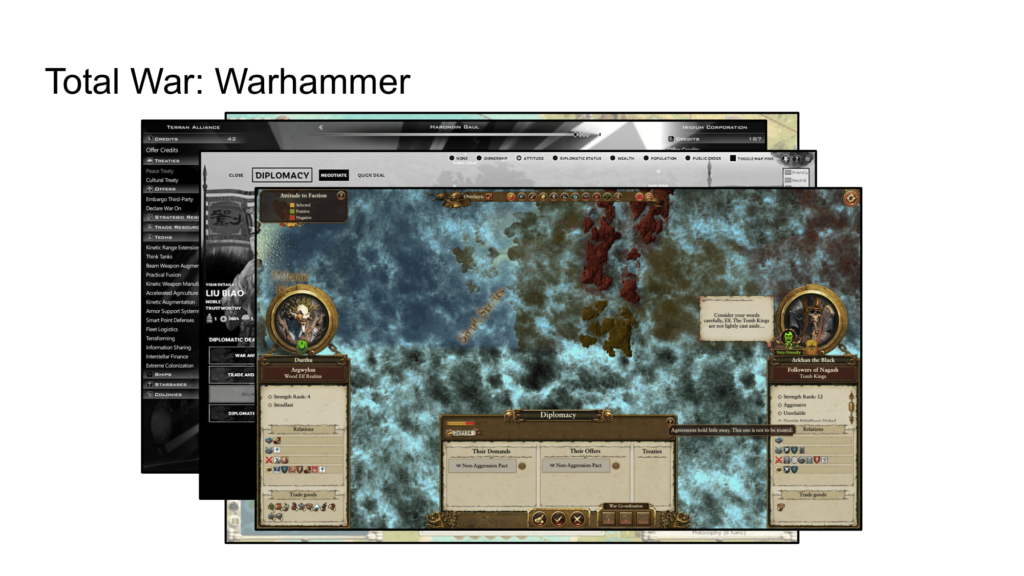

In Total War: Three Kingdoms.

In Total War: Warhammer.

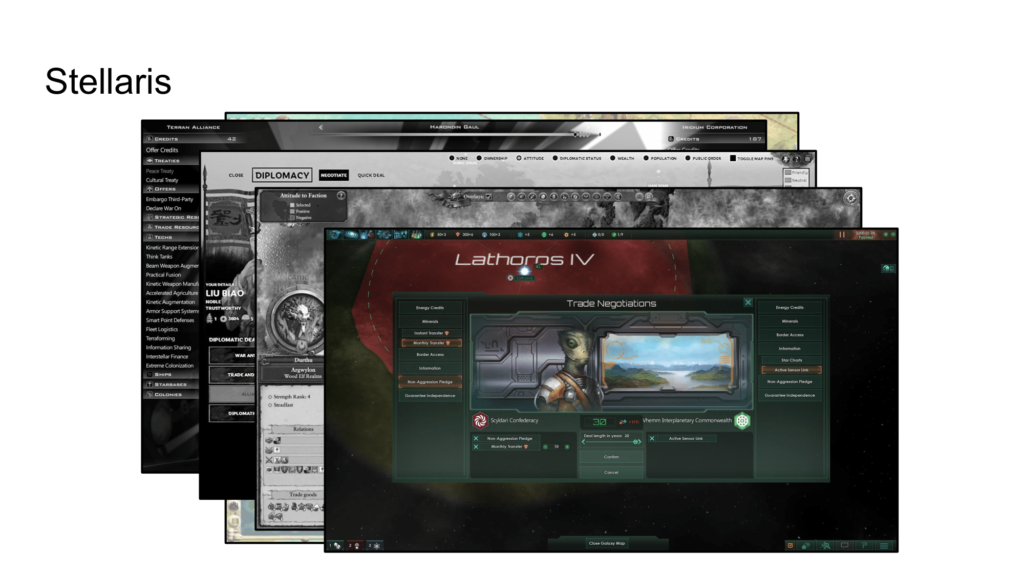

In Stellaris.

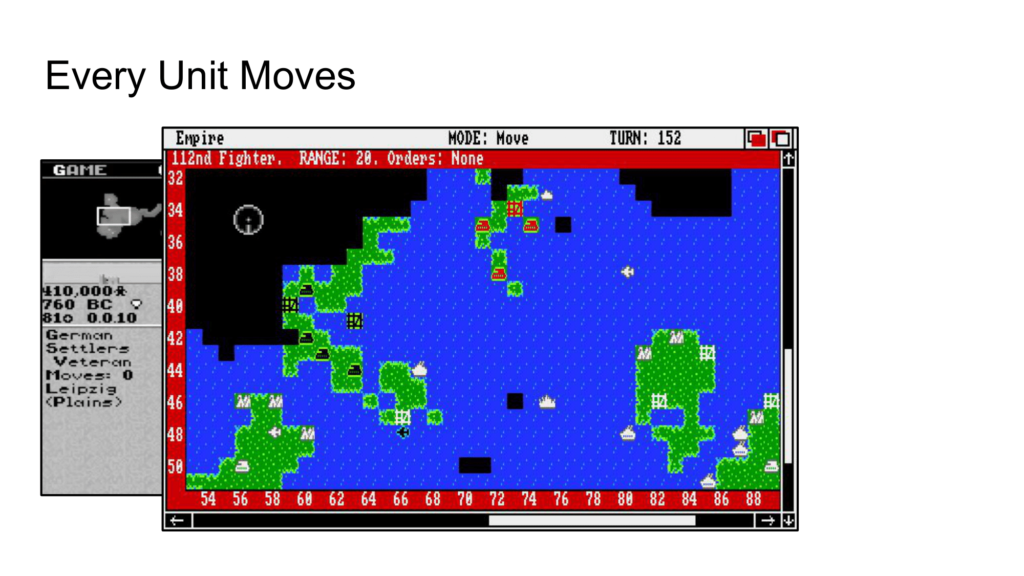

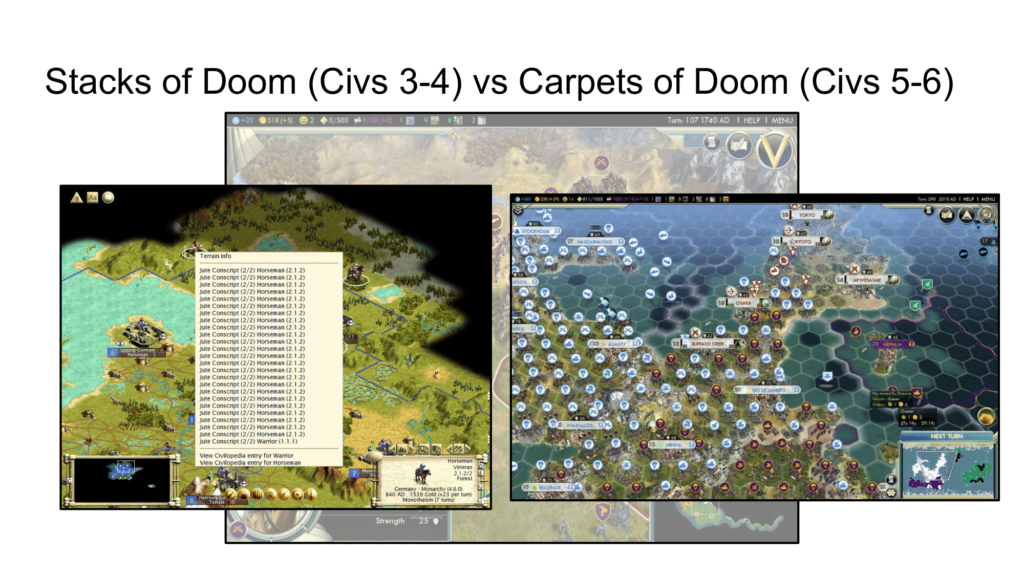

Unfortunately, it was a big mistake. My first inkling there was a problem was after Civ3 shipped and people started to complain that the AIs all tended to have the same techs. The reason was that the AIs were using the bargaining table the same way humans did – every time they got a new technology, they would contact all of their friends, rivals, and even enemies to see what they could get in return by trading it away – which cost them nothing but could get them a little something in return.

From the human’s perspective, it looks like the AIs were part of a giant tech cartel and were selling techs to each other at bargain prices, but the AI was simply pursuing the optimal strategy. Again, we have a system where players were ruining the games for themselves because there was no cost to contacting every civ every turn and also endlessly tinkering with how to get the best deal possible. No reason not to put just one more gold piece on their side of the table until you’ve hit the AI’s maximum price for what you are trading away.

There are ways to mitigate this issue, but this is a Cursed Game Design problem as defined by Alex Jaffe in his fantastic 2019 GDC talk, which I recommend everyone should take the time to watch. There is a conflict here between the power and flexibility of the bargaining table and the give-and-take of real diplomacy where flawed personalities come into play and you can’t nickel-and-dime a rival without offending them.

Ultimately, we come back to this – there is no solution here because we are giving the player all the tools to ruin the game for themselves.

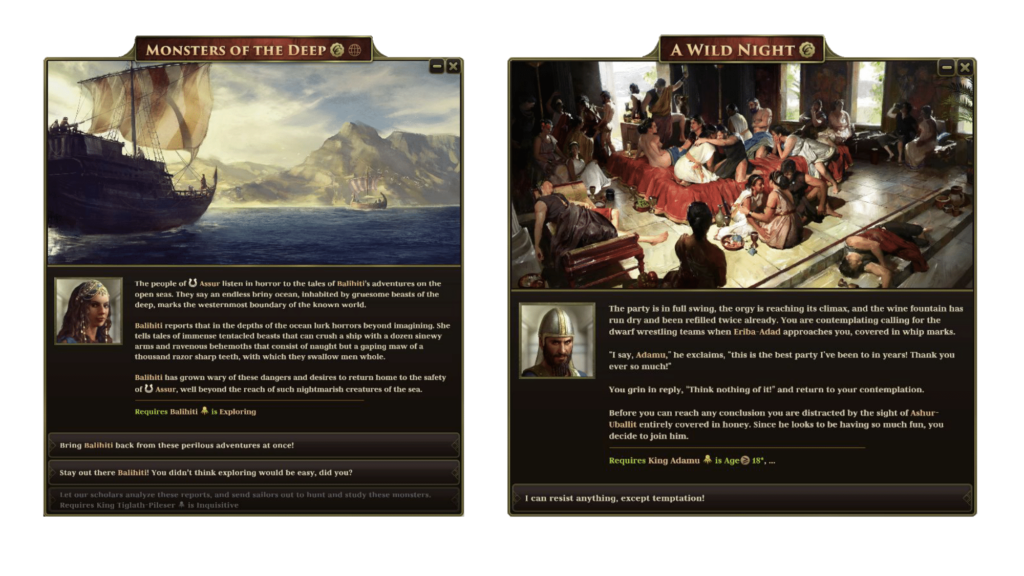

Fortunately, Old World had a system in place that could solve this problem by replacing the bargaining table with something else – the Event System! Here is one example – you married a Babylonian many years ago and now because of that connection you must choose a side in the war between Babylon and Carthage.

This system presents the player with interesting diplomatic events and choices that react to the current game state, serving up possible paths to war at a pace that is healthy for the player. Getting rid of the bargaining table was a risky decision because players expect it by now, but the end result could be so much more dynamic and interesting and free the player of the burden of trying to min-max the table. So, when you ask another nation for a truce or for a trade mission or to start an alliance, the game gathers all the events with those specific triggers, throws out the ones that are not applicable to your current situation (such as the events that require a child ruler), and then randomly picks one to present you. Angry nations are still less likely to want to trade with you, but the actual result of a trade mission will still be unexpected, making it a worthwhile gamble to take.

In this example, you can get out of a war if you captured a hostage during combat – a good example of the loosely coupled events I mentioned earlier.

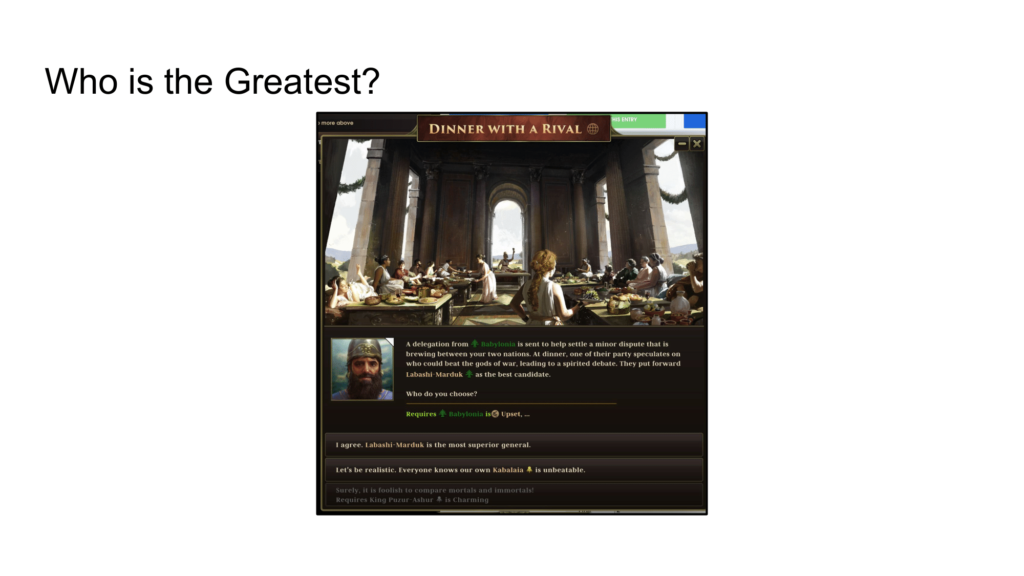

In this example, based on a story from Livy of a meeting of Hannibal and Scipio Africanus after the end of the second Punic War, you are forced to choose who is the best general, either one of your own or one of theirs. You must choose between damaging your own legitimacy or angering your guests. These incidents stir the pot of diplomacy and make the game dynamic.

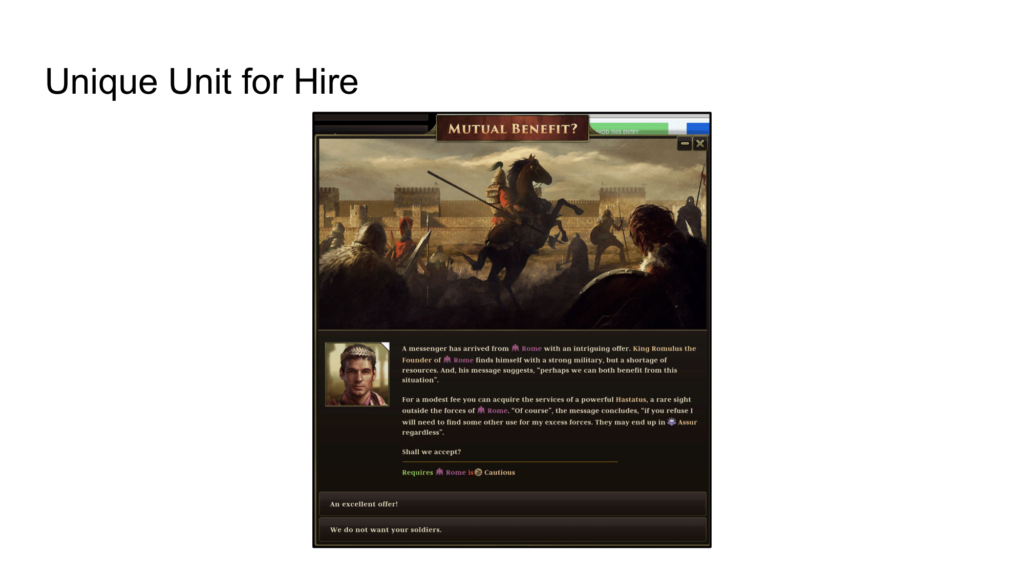

Here, Rome is offering you one of its unique units, a Hastatus, as a Mercenary, a good example of something we’d be afraid to put on the bargaining table because it would be abusable, but it works fine as a random event which isn’t guaranteed to appear.

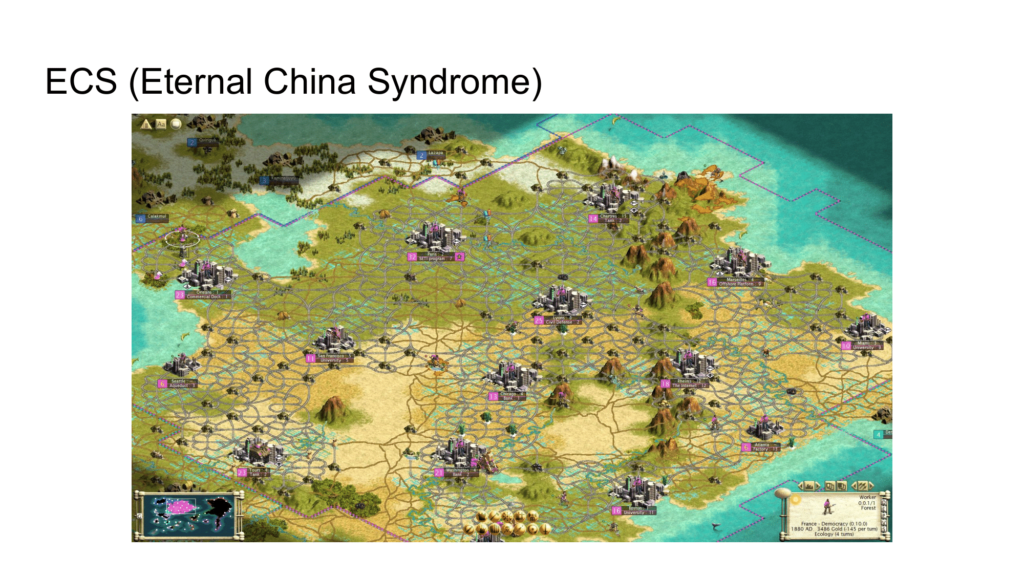

Now, here is the great beast, the biggest design challenge for every 4X out there – how to bring the game to a satisfying conclusion after hundreds of turns and an untold, perhaps embarrassing, number hours in front of the computer. I view Victory Conditions as a necessary evil; for awhile, I had hoped that maybe we could do without them altogether, like the Paradox Grand Strategy games do. No one really cares about winning or losing those games, it’s all about the experience, MAN, so maybe victory conditions had become old-fashioned. Maybe I was old-fashioned! The truth is that games like Crusader Kings and Europa Universalis are really more like simulations than they are like games, and one important fact about 4X games is that they are g-a-m-e-s games. Players expect to win, or give up trying.

One thing I did not want to inherit from the Civ series was themed victories – another thing that I helped get rolling back with Civ3 which added Cultural and Diplomatic victories to the traditional Conquest and Space Race. The problem with themed victories is that, because they require a high bar, the player has to aim for them early on, which warps all the decisions made over the course of the game. Aiming for the religious victory? Make sure to always make the religious choice each time you get it as an option! Thus, I needed something more, well, generic, and I needed it quickly because we were playing Old World as a multiplayer game within the first six months of the project.

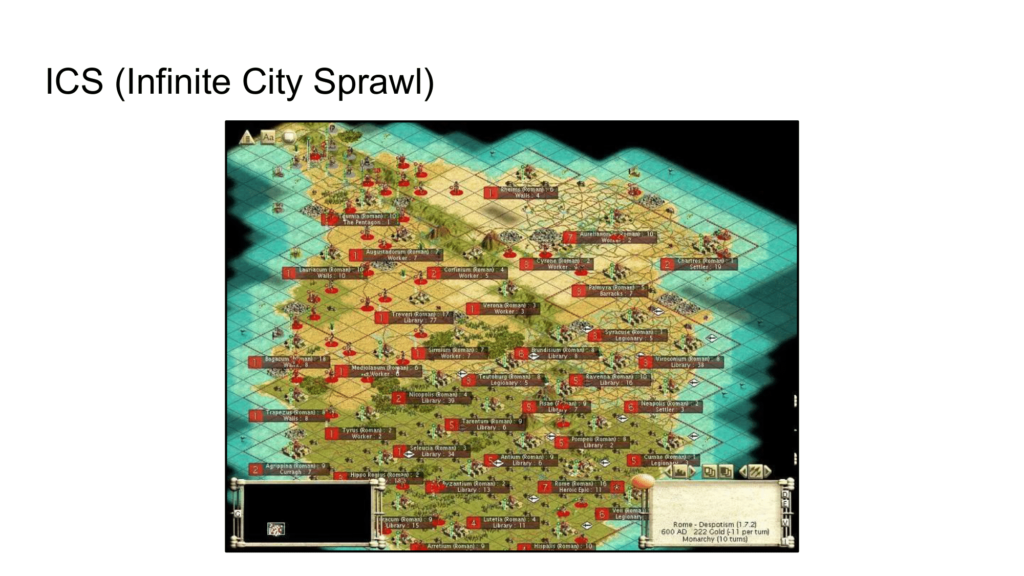

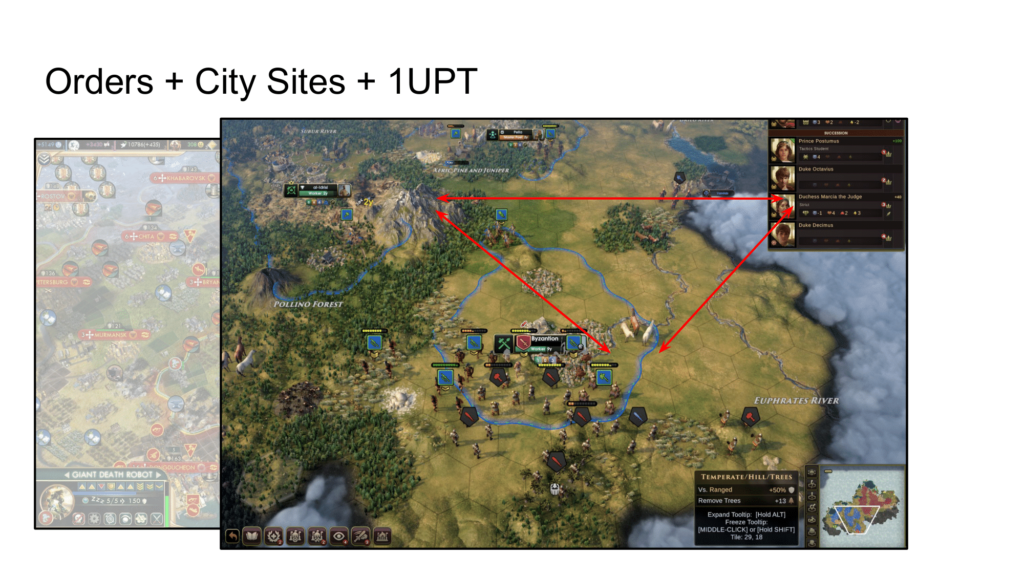

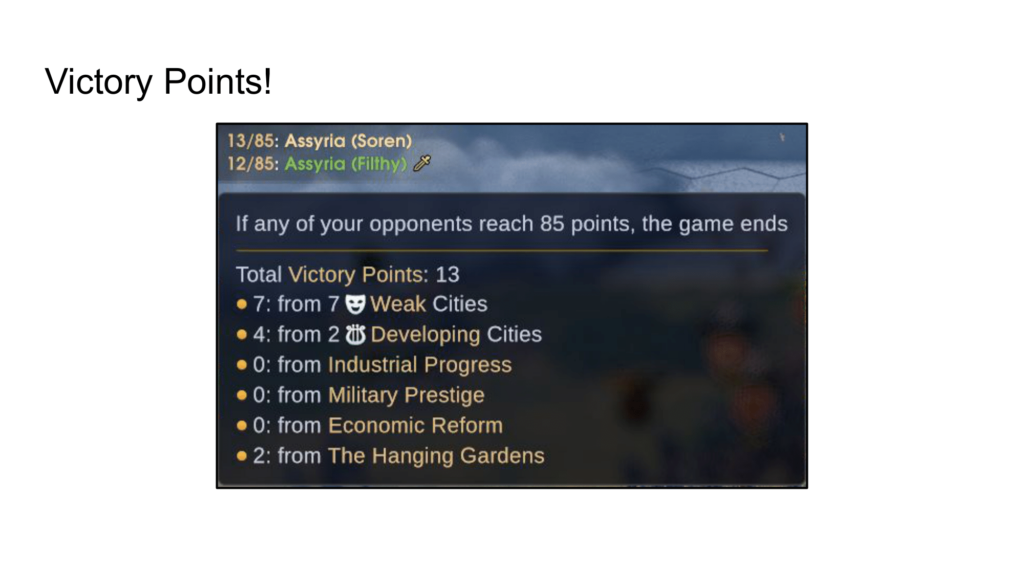

So, I went for the most boring solution possible – victory points – and it worked out surprisingly well. The reason it worked is because we tied them to city sites – which were a known quantity because we determined how many sites there were at the beginning of the game. If a 4X game without city sites had a victory condition that simply required X cities to win, then it’s no mystery what would happen – the game would have the worst case of ICS ever as players would be cramming cities everywhere. Instead, because we knew that a specific map had only 30 city sites on it, it became easy to pick some threshold which would trigger victory.

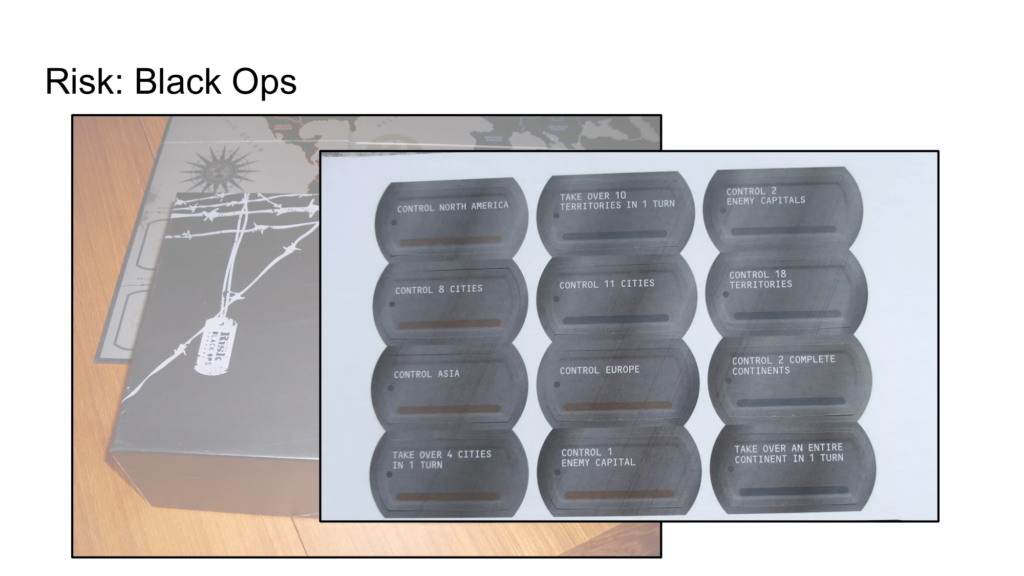

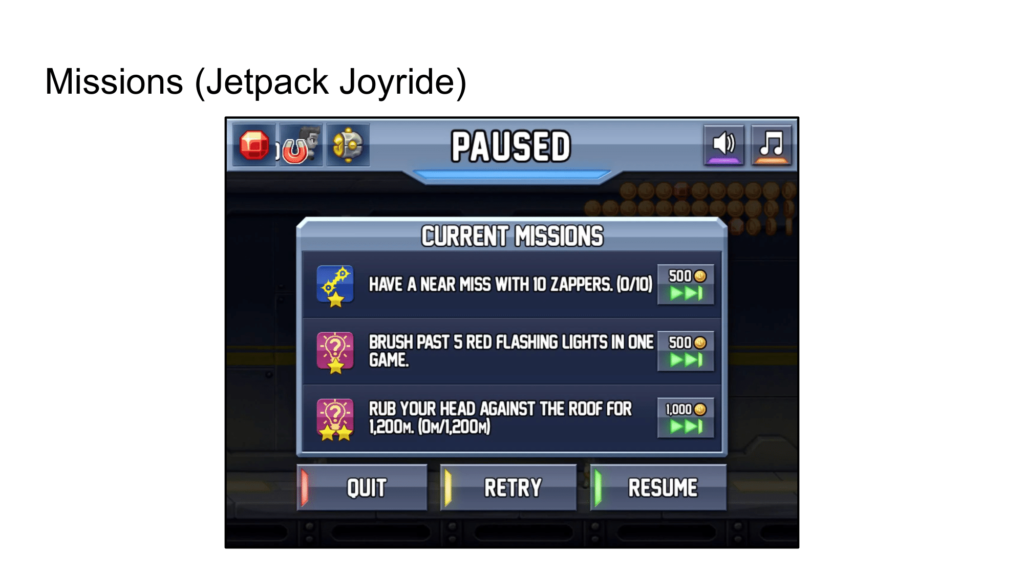

Of course, while victory points are a perfectly serviceable win condition, they hardly fire the imagination, so we needed something a little more interesting, a little more thematic. I wanted a victory condition that dynamically told the story of your dynasty and hopefully even pushed you to play a little differently. I found my inspiration for this from Jetpack Joyride, which had a mission system that encouraged you to achieve one of three random goals, often ones that forced you to play the game differently. Our initial ambition system worked just like this, three random ambitions which give a bonus upon completion and which get replaced by slightly more difficult ones.

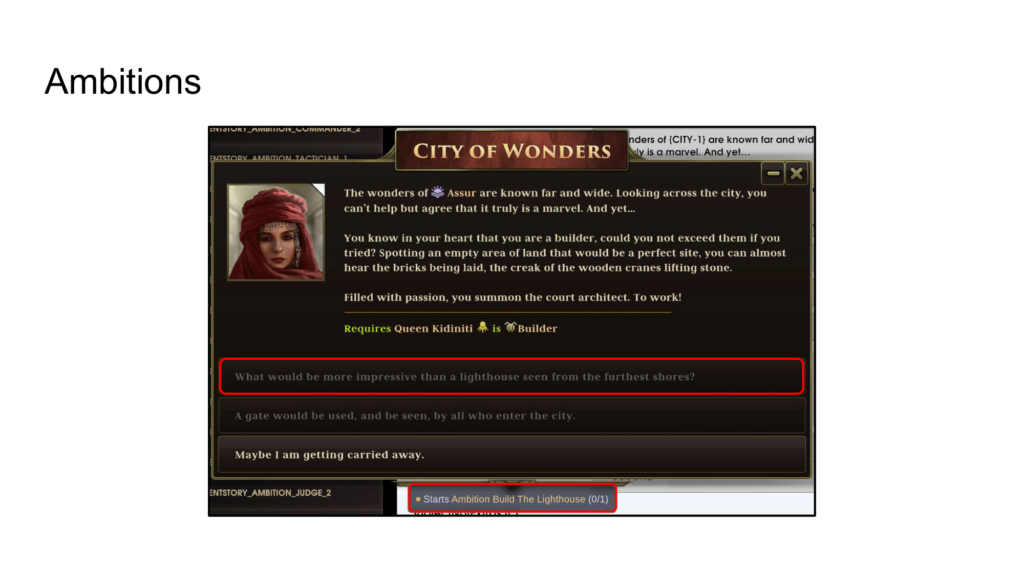

Eventually, we made these part of the character system as the Ambitions would be attached to your leader, similar to how it works in Crusader Kings. Further, the Ambitions that come up would be related to the current game state. In this case, the leader is a Builder, so she gets Ambitions to build Wonders. However, they were not initially part of the victory system.

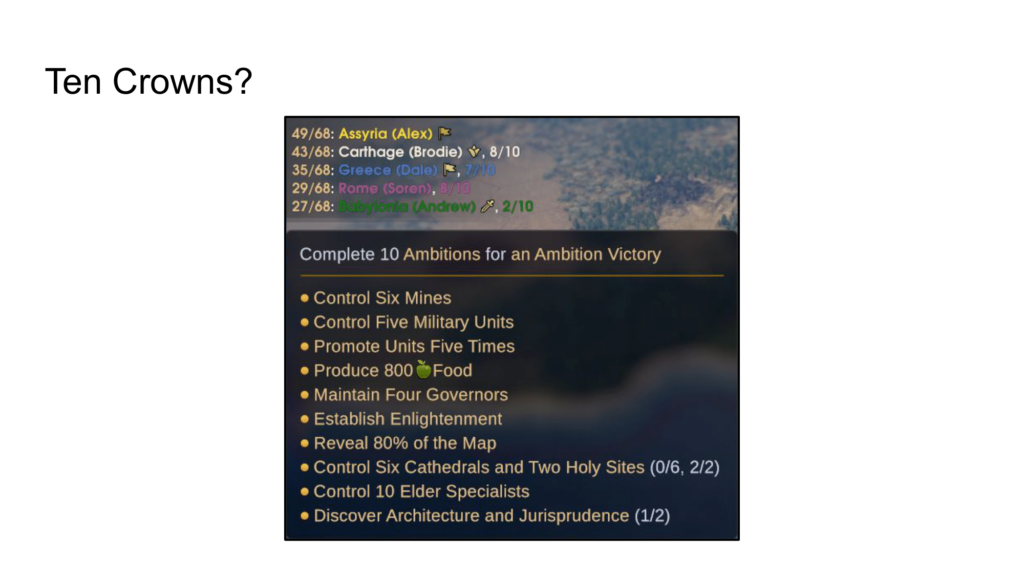

In fact, the initial reason I tried turing Ambitions into a Victory Condition was actually to save the original name of the game, Ten Crowns. The name initially meant that you had ten lives to play the game, ten rulers before the game would end, but that proved too hard to work out in practice as ten rulers could last 50 turns, or they could last 500. Thus, I tried to retcon the name by renaming “Ambitions” to “Crowns” and then the victory condition would be right in the title! However, the team didn’t buy it, and we of course shipped with a different name.

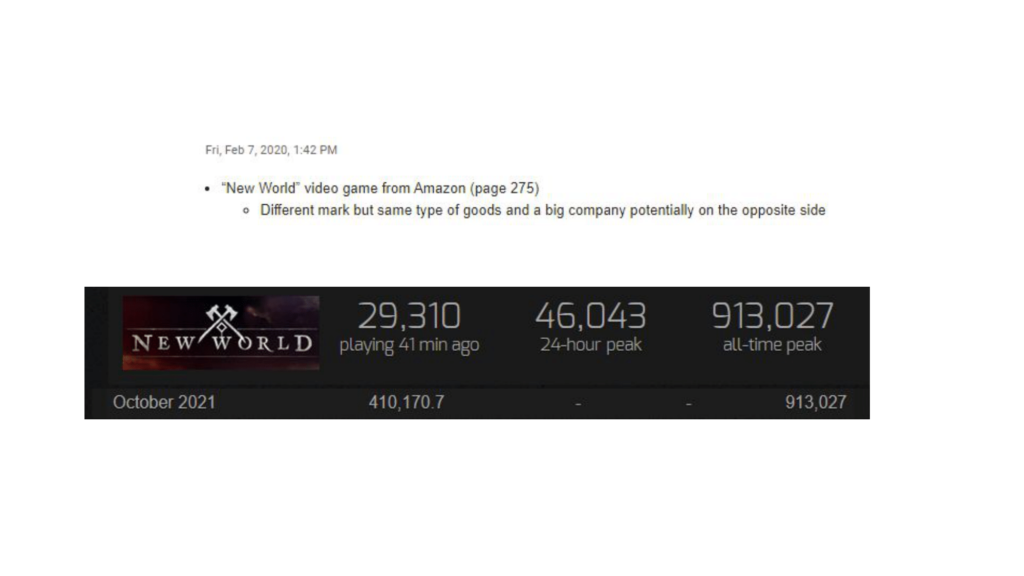

Speaking of which, when we ran the trademark search for Old World, we got a one-line note from our lawyer that Amazon had reserved the word New World for some upcoming video game. I didn’t give it much thought because how often does Amazon actually ship their games…

…yeah, it was fun trying to spend the end of last year explaining on Twitch that we weren’t some weird prequel to New World.

So, the game would be called Old World, and we now had a simple, thematic victory condition – fulfill ten ambitions picked by the rulers of your dynasty and win the game. However, one issue I have often seen with the themed victories of Civ is that, because they can focus on internal progress that is not visible to other players, when one player achieves a Cultural or Religious or Scientific victory, it can some as quite a surprise, and I don’t believe a player should ever be surprised by a “You Just Lost” popup after a twenty hour game. So, we made the simple decision that the AI could not win via Ambitions, they could only win with victory points, which are much more straightforward (and always visible in the upper-left corner).

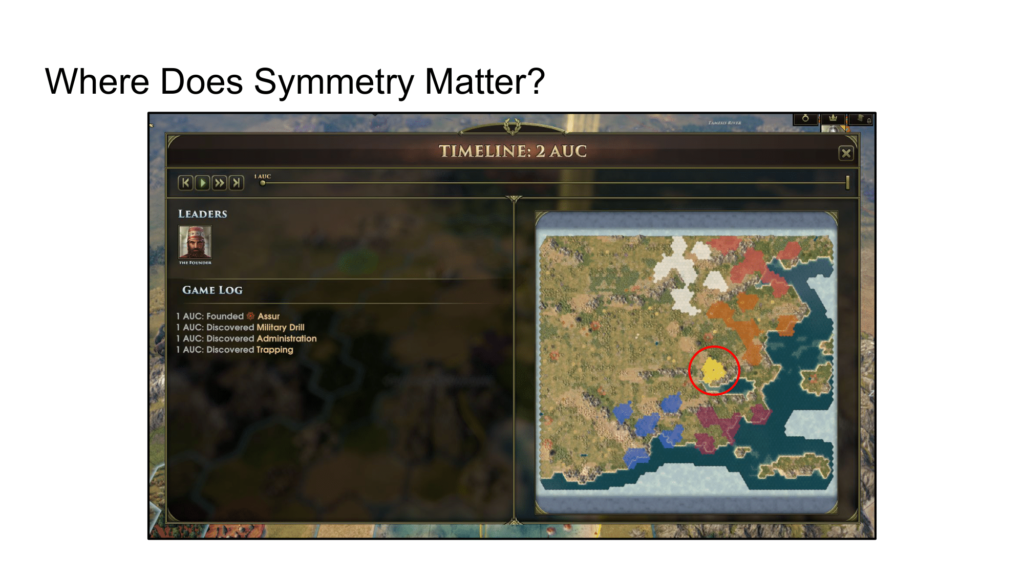

This type of asymmetry is unusual in a 4X game where the AIs are ostensibly supposed to be stand-ins for human players, but that’s always been a myth. Players don’t actually want the AIs to behave like humans – as a simple example, real human players would usually all gang up on a player who is coming close to victory, regardless of previous relationships. However, if you have the AI behave that way, players will accuse it of treating the human unfairly, of not letting them win fair and square. There’s nothing inherently better about symmetrical design – indeed, I’d say much of the most interesting work in the tabletop renaissance is with deeply asymmetrical games like Root or the COIN series.

Once we broke the seal of asymmetry, it opened up the design space significantly. The AI, for example, doesn’t get events because we wanted events to have meaningful results. It’s ok for one of YOUR events to end a war because you convinced the AI’s heir to seize the throne – however, it wouldn’t be ok for that to happen to you just because the AI drew that event. Trust me, that may sound interesting theoretically, but it’s not going to go down well with players. Further, without symmetry, we could rethink difficulty levels. Instead of giving the AI bonuses, like faster research or cheaper troops, we simply start the AI with more cities than you.

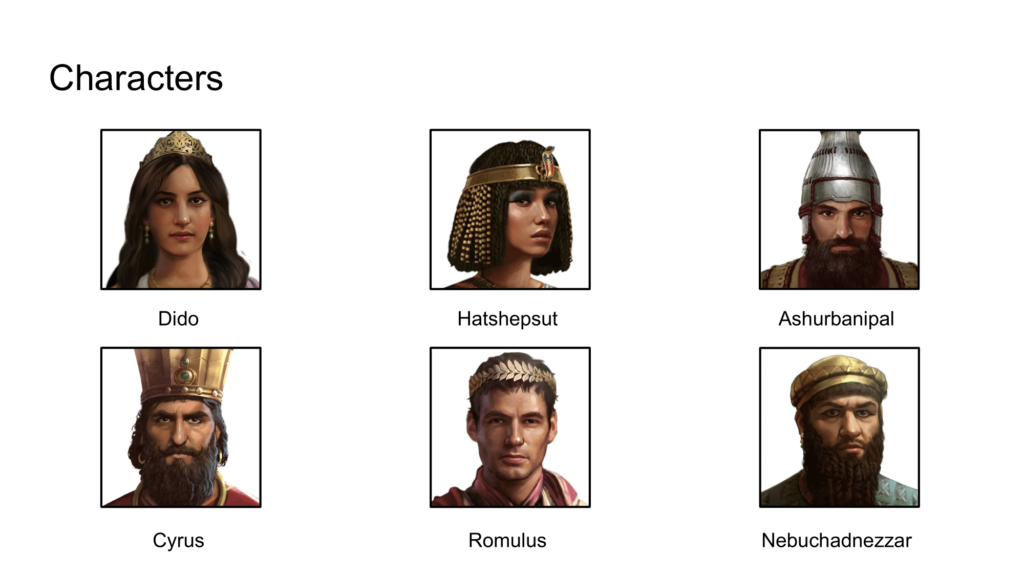

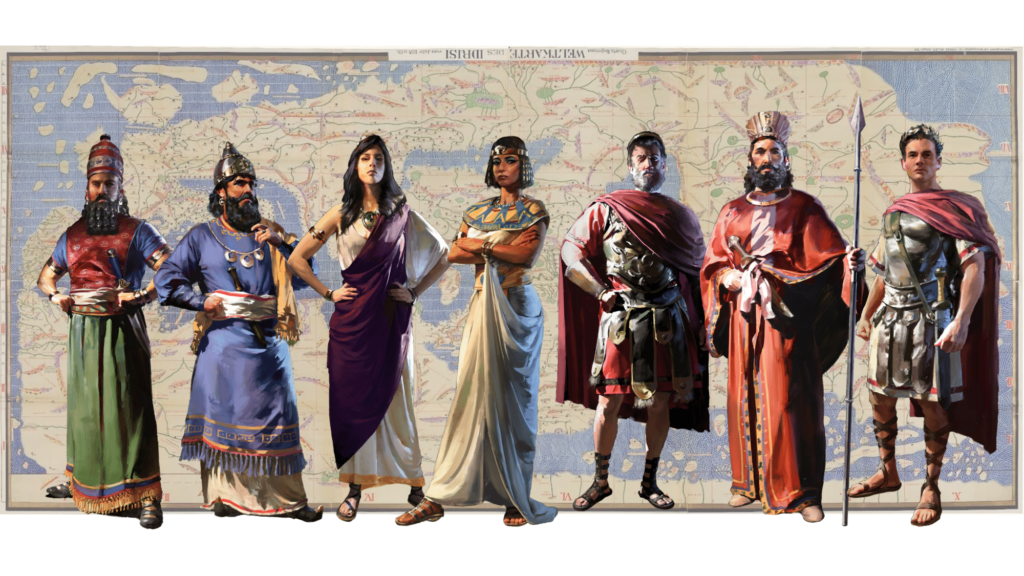

Thematically, you are a new nation in an Old World, somewhat like Rome was in the fourth century BC, a small kingdom centered on one city and surrounded by larger, more ancient empires like Greece, Egypt, Persia, and Carthage. Thus, the AI in Old World plays without any bonuses or cheats at all, simply with a significant head start depending on the difficulty level. We felt players would enjoy knowing the AI was playing by the same rules as the player while also finding a way to provide a challenge for veterans.

Maybe this is a better animal themed metaphor for where I am now as a designer. I’ve gone deep on 4X games during my career. I probably know more about these types of games, what works and what doesn’t work, than is really healthy for a person. My design journey with Old World was truly about putting that knowledge to good use, to not let it go to waste, so that we could push the genre forward in an intelligent, considered way.

Often the best source of innovation is from new blood coming into the industry with new ideas, but I’d like my work now to show that it’s possible to innovate after 22 years in the industry as long as you’re willing to give an honest assessment of what parts of your games have been making players’ lives better and which parts have been making them worse. Many of the mechanics and systems from Civ that I’ve rejected with Old World are ones that I came up with myself. The bargaining table and themed victories, cultural borders and strategic resources, are ideas that I pushed for when I was 24, just out of college.

Old World is a conversation with myself as a younger designer, and I feel fortunate that I got the opportunity to have that conversation. Opportunities like this don’t come along everyday.

Thank you.