I gave a talk on games and meaning at GDC 2023, which is now available on YouTube:

However, I fully scripted the talk ahead of time, so I decided it would be worth taking the time to post the slides online, in three parts to have mercy on your browser.

Conflict between designer intent and player behavior actually predates video games as it is a common issue with historical wargames. One of the basic challenges of wargame design is how to encourage historical play when no one knows what the likely or even plausible alternate results could be – for example, could the South have ever won the Civil War? – and how to recreate the pressures that led to bad decisions even when we all know the outcome. Maybe Napoleon should have known better than to invade Russia, but even my kids know not to start a land war in Asia.

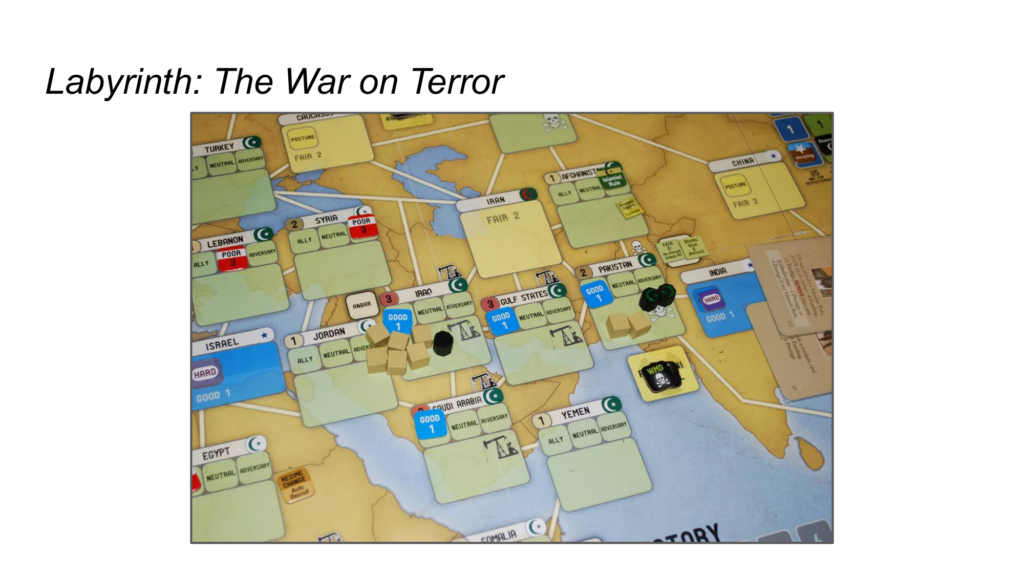

A good example of this problem is Volko Ruhnke’s Labyrinth, a game about the War on Terror that starts in 2001 and pits the US against Al-Qaeda. It must have been a difficult game to design for many reasons, one of which is that many of the US’s historical actions, such as the invasion of Iraq, backfired horribly, which players would presumably want to avoid. However, when you read the rules for the game, it comes across like a Bush administration neo-con fantasy world. The mechanics enable a domino effect of Western support throughout the region. Establishing a democracy in one Middle Eastern country will cause it to spread to its neighbors, just like we were told would happen in Iraq back in 2003. When I first encountered the game, I was a little shocked, because it is easy to assume that the designer had fallen for this neo-con propaganda.

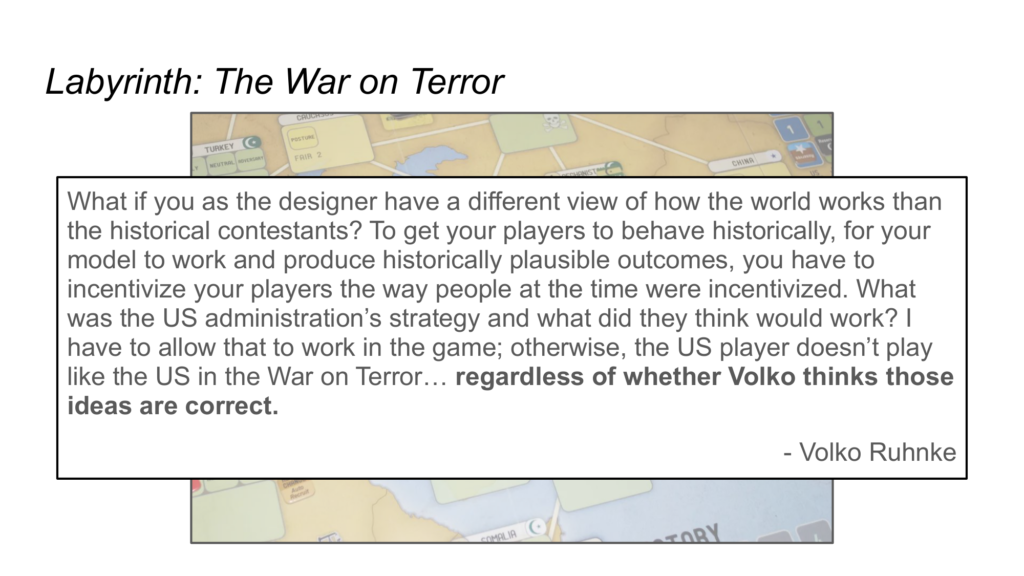

Years later, the designer actually addressed that question head on:

What if you as the designer have a different view of how the world works than the historical contestants? To get your players to behave historically, for your model to work and produce historically plausible outcomes, you have to incentivize your players the way people at the time were incentivized. What was the US administration’s strategy and what did they think would work? I have to allow that to work in the game; otherwise, the US player doesn’t play like the US in the War on Terror… regardless of whether Volko thinks those ideas are correct.

This raises the question of what is the point of a historical game? Is it an attempt to model history? To actually experiment with alternate outcomes? Or is it to help us understand why people made decisions that we find baffling or shocking today? With Labyrinth, Ruhnke is not trying to recreate history; instead, he is trying to recreate the historical mindset of the time. As we’ve covered, the ability of a game to simulate the actual world is extremely limited and, thus, misleading. Labyrinth shows a clear example of an alternative – simulating the pressures, the desires, and the fears of historical actors, which can be much more illuminating. The study of the past is not just about what people did but also about why they did it, and a game can probably do a better job of teaching the question of WHY people made choices they did than any other medium.

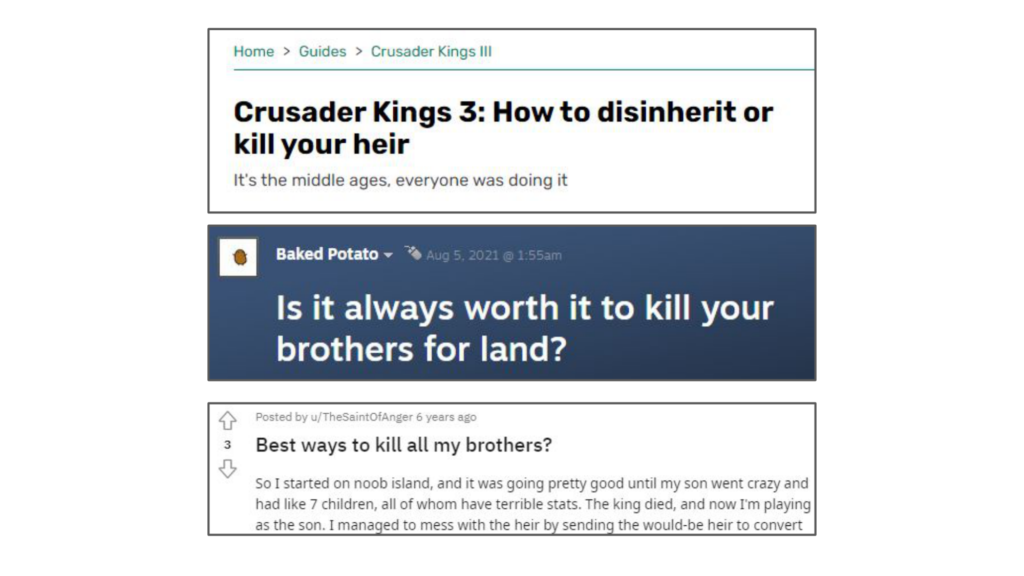

Let’s move that question to a different era, the medieval world of Crusader Kings. Now, they could have made the game with a very different focus – maybe how best to conquer the world or what is the fastest way to advance out of the Middle Ages – made it more like Civilization, in other words. Instead, they leaned into empathizing with medieval rulers, putting you under the same pressures that made it difficult to maintain a dynasty and keep you realm from fracturing. Which leads to…

…lots of posts like these. How to kill off your heir? Is it worth it to kill off your brothers? Indeed, what is the best WAY to kill off your brothers? Now that’s an interesting question for players to ask because…

… fratricide was actually official policy during a certain period of Ottoman history. For example, when Selim I assumed the throne in 1512, he quickly executed his two brothers. Mehmed III had 19 of his brothers and half-brothers murdered. Eventually, they began imprisoning their family members instead, which was quite an improvement. So, Crusader Kings certainly meets Ruhnke’s goal for a historical game, to encourage players to behave historically regardless of what the designers at Paradox think, who presumably have neither killed nor imprisoned their own brothers.

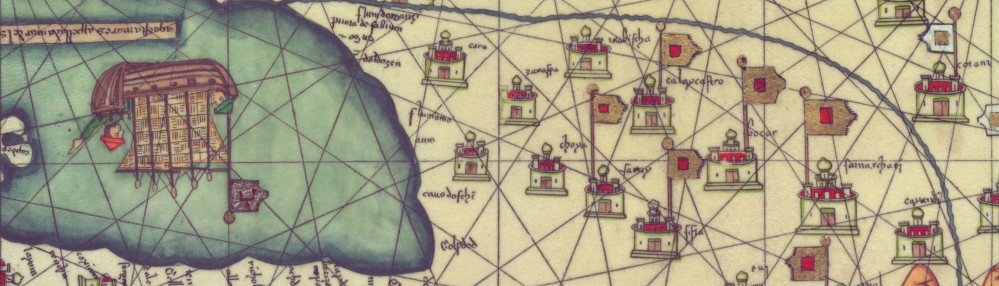

It requires creativity for a game to recreate a historical mindset as opposed to being just a historical re-enactment. For example, Europa Universalis includes a Randomized New World mode which makes the game less realistic but instead more true to the human experience of the age, of being an explorer and not knowing what is over the horizon.

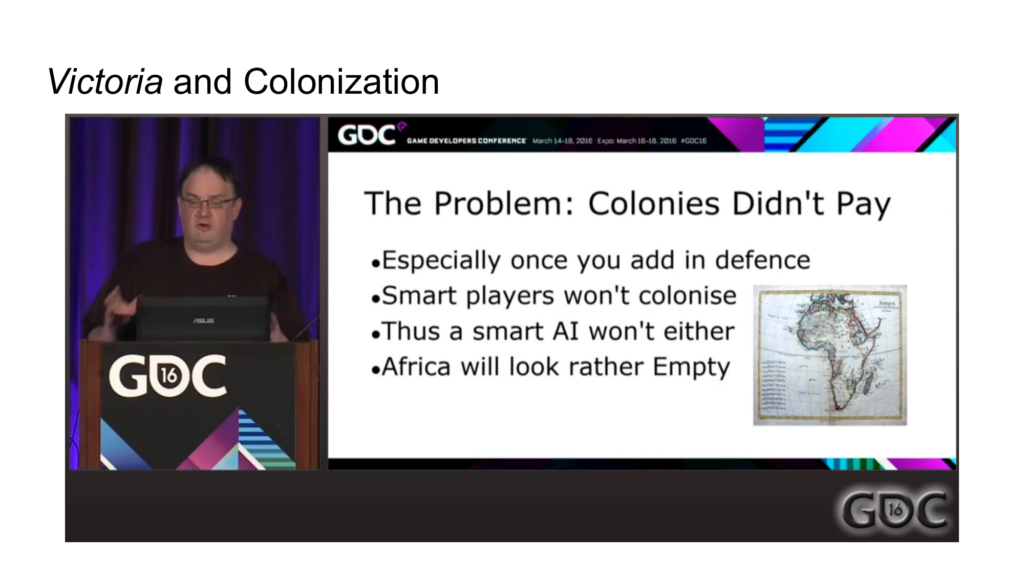

There is a similar issue with Victoria, which designer Chris King outlined a number of years ago. Historically, colonies just didn’t pay. They tended to be a net-loss for the controlling countries as it cost more to subjugate, manage, and defend than it brought back home to the colonizer. However, a game about 19th Century Europe in which those nations did not race for colonies, even if to the detriment of literally everyone in the world, would clearly put players in an ahistorical mindset. In Victoria, they solved this problem by making colonies a necessary part of their economic model, providing the raw goods and, eventually, markets that the player’s factories and businesses needed. It’s not a realistic model of history, but it is a realistic model of what 19th century Europeans thought was important to them at the time.

An important consideration here is whether players will understand the line between the game incentivizing historical behavior and the game espousing a world view.

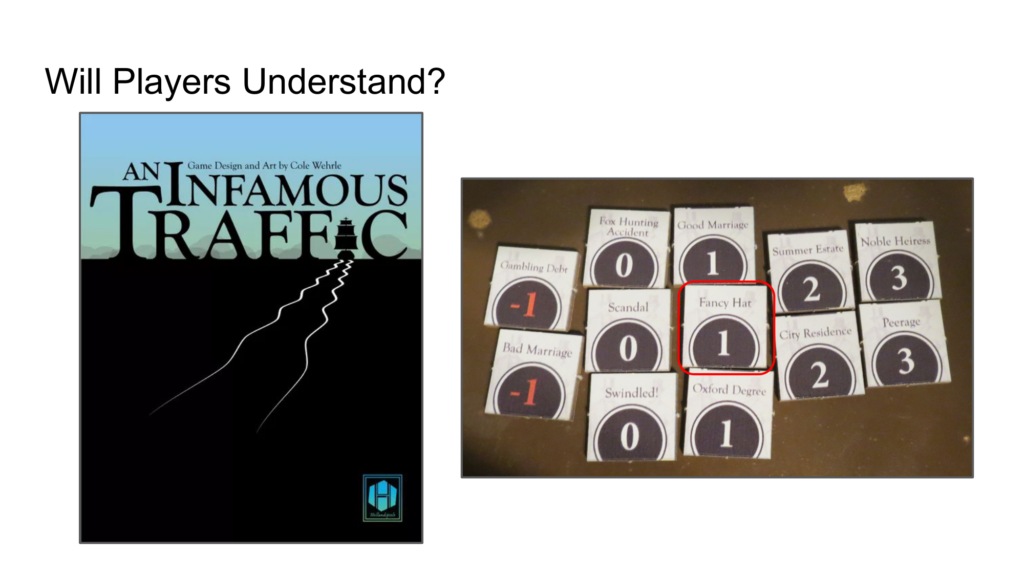

In Cole Wehrle’s An Infamous Traffic, you play English aristocrats who are profiting from selling opium in China during the 19th century. You are playing bad people doing bad things, and the designer underlines this by how victory works. The money you earn in China gets converted into frivolous prizes back home in London, including my favorite, a Fancy Hat. The game is telling you that it knows you are doing bad things, and you shouldn’t feel good about the fancy hat you ended up with as your prize. A game’s framing can matter a great deal to help players separate a historical mindset from actual reality.

What if, at the end of Civilization, instead of telling you how much land you conquered, the wrap-up screen told you how many cultures you destroyed and how many languages have disappeared?

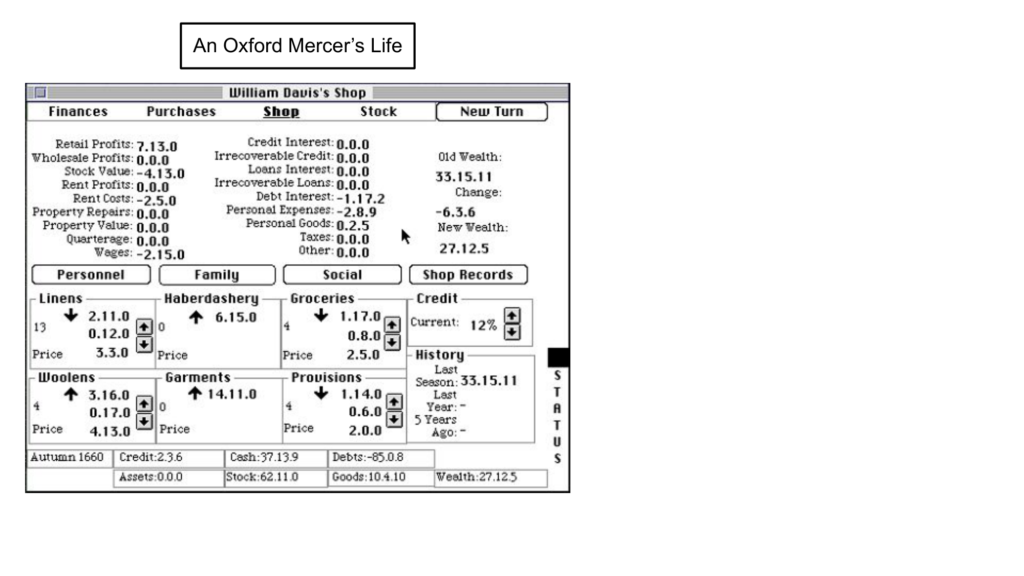

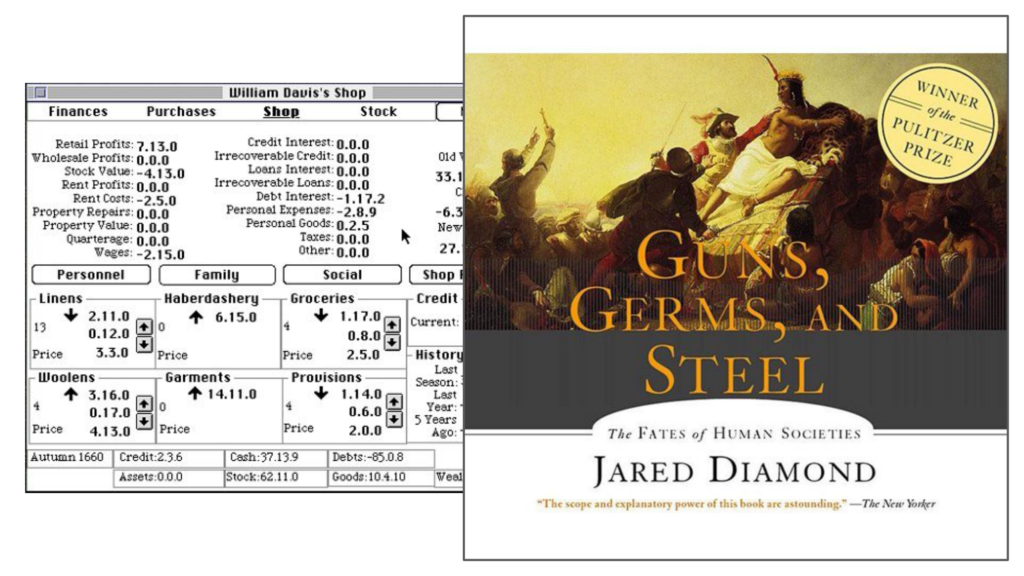

I started my career very passionate about making games about history, games that could sit next to a book or a documentary as a legitimate secondary source on world history. My history thesis paper in college was a game that simulated the life of a shopkeeper living in early modern Oxford, based on my research in the Oxfordshire Archives. It didn’t just model the change in prices over time but also your standing in the local Mercers and Grocers Guild as well as your family life as the line between personal and business affairs was not as fixed back then, so you have to worry about your children and their future.

Two years later, I started working on Civilization III, and I was super pumped. I had just read Guns, Germs, and Steel and was inspired to make the videogame version. However, I quickly ran into the goofy reality of video games, of how players will twist your games into what they want to play. I learned that you can’t just put Horses and Wheat and Pigs on one continent but not on another and expect players to be ok with starting in the wrong place.

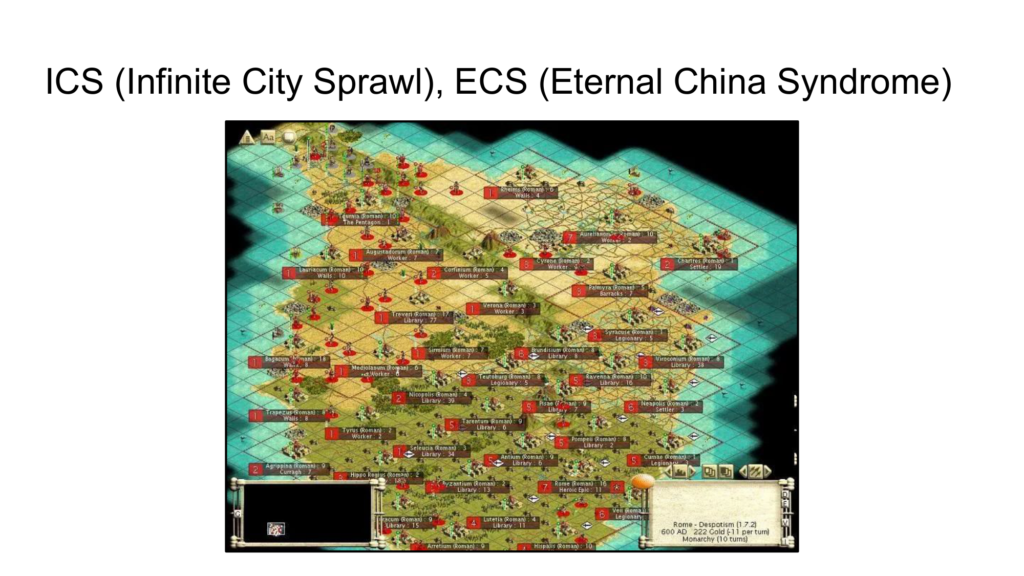

And then I met the twin evils of Civilization, Infinite City Sprawl, which is how the game encourages cramming cities into every possible spot on the map, and the Eternal China Syndrome, which is how once the initial expansion phase is over, the game becomes static and dull. These effects have nothing to do with history and everything to do with players seeing past the historical setting to the game’s inner math.

So, after making Civ 3 and abandoning the idea that I was making a history simulator, I had to ask myself, what could I actually communicate with Civ 4. Why make that game at all? In doing so, I started down a path that led me to why I make strategy games.

Here is the Civ 4 Civics screen. In Civs 1 through 3, you adopted an ideology – Monarchy, Despotism, Communism, Democracy – which came with a bunch of bonuses and penalties, basically judgments on the designer’s part on what those ideologies meant. I dropped that entirely for Civ 4 and implemented a build-your-own-government system where you choose where power lies, the type of economy, how the legal system works, and so on. You could have a Police State with a Free Market or you could have Slavery mixed with Free Speech. Or you could mix Universal Suffrage with State Property. The whole point was to defy ideological labels to get the player to see past them.

If the twentieth century has a single theme, it is that ideology itself is a failure. Dogmatic leaders used ideologies to demonize the “opposition,” which usually meant helping the strong to terrorize the weak. From Nazi death camps to the Soviet gulags to China’s Cultural Revolution to America’s McCarthyism, the twentieth century was full of ideas that gave power to autocratic leaders not afraid to destroy the lives of those who resisted. Much as we hate to admit it, these leaders were often supported by masses of people who believed in the stories these leaders told, the ideologies they espoused.

Demagogues love the labels that ideologies provide because they obscure and dehumanize the opposition; both sides of the Cold War made liberal use of the terms “Communist” and “Capitalist” to define and differentiate each other, even though the United States government has slowly adopted communist programs piecemeal over the last century. Why exactly was the U.S. – a country with social security, medicare, welfare, a minimum wage, labor laws, and trade unions – killing people to keep Communism out of Vietnam? In fact, if you took a typical Red-fearing, union-busting industrialist from 1923 and sent him 100 years into the future and explained to him how America works now, he would probably assume that the Communists won after all!

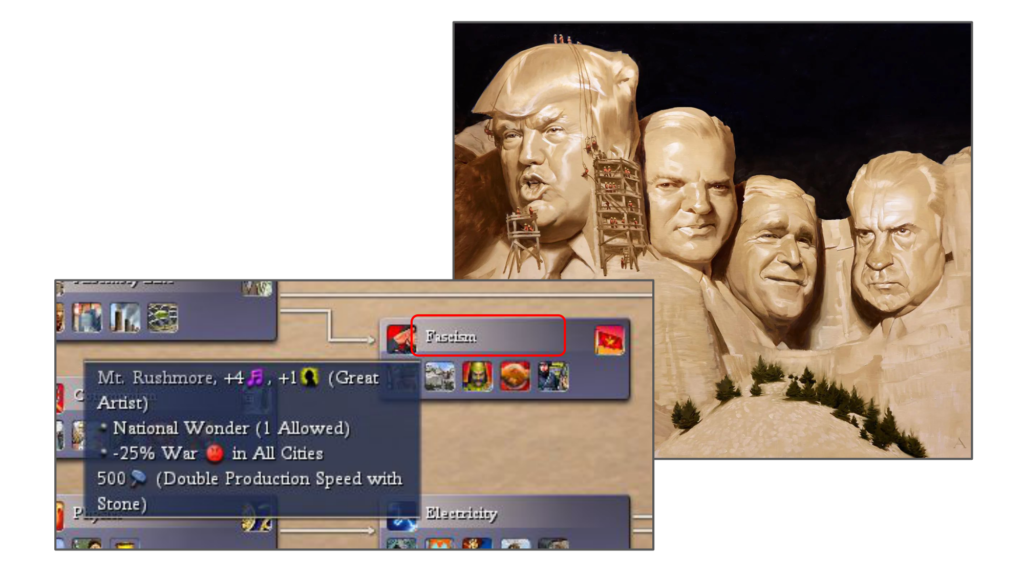

Labels exist to separate and control people, and I wanted the civics system to encourage people to look past the labels and at the actual choices a society needs to make when governing itself. It was no accident that I attached Mt. Rushmore to Fascism; carving mammoth statues of your country’s leaders into a MOUNTAIN is fascist, even if we do not live under capital-F Fascism. Our own self-labeling as a Capitalist Democracy does not protect us from charges that our country is damaging the world when our policies hurt real people.

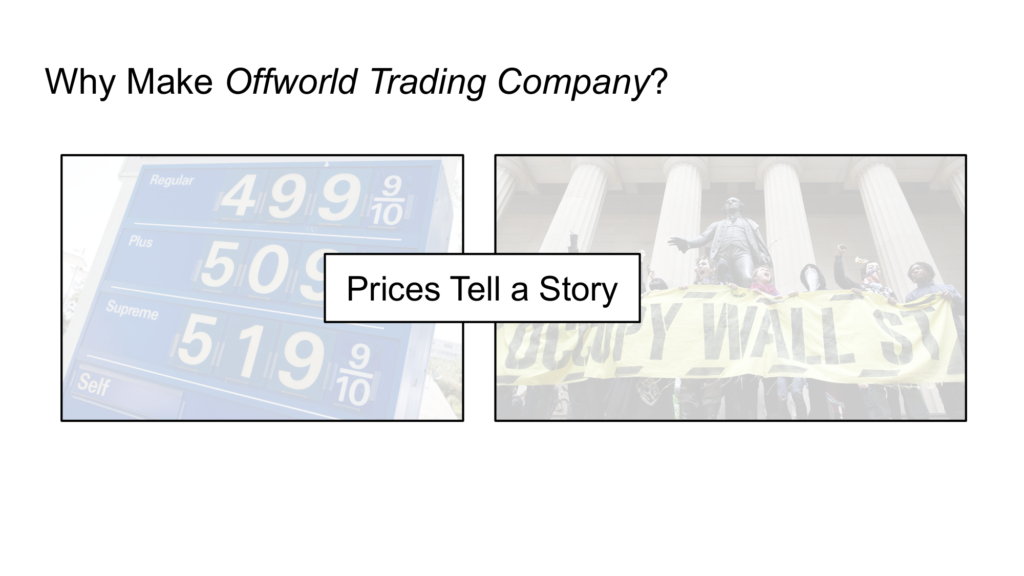

I often get asked whether Offworld is a free trade game or an anti-capitalist game or some other statement on the world economy. I don’t think games should make broad statements like “capitalism is good” or “capitalism is bad” – it’s just too simplistic, and as we’ve discussed, injecting a heavy-handed message can so easily go off the rails.

In Offworld, if Iron costs more than Steel, something has gone wrong, and you win by taking advantage of those discrepancies. There is a reason why everything costs what it does. Sometimes, that goes beyond just supply and demand to government policy and cultural factors, but there is always a reason, and if we don’t like what something costs, we should find out why instead of just complaining about it.

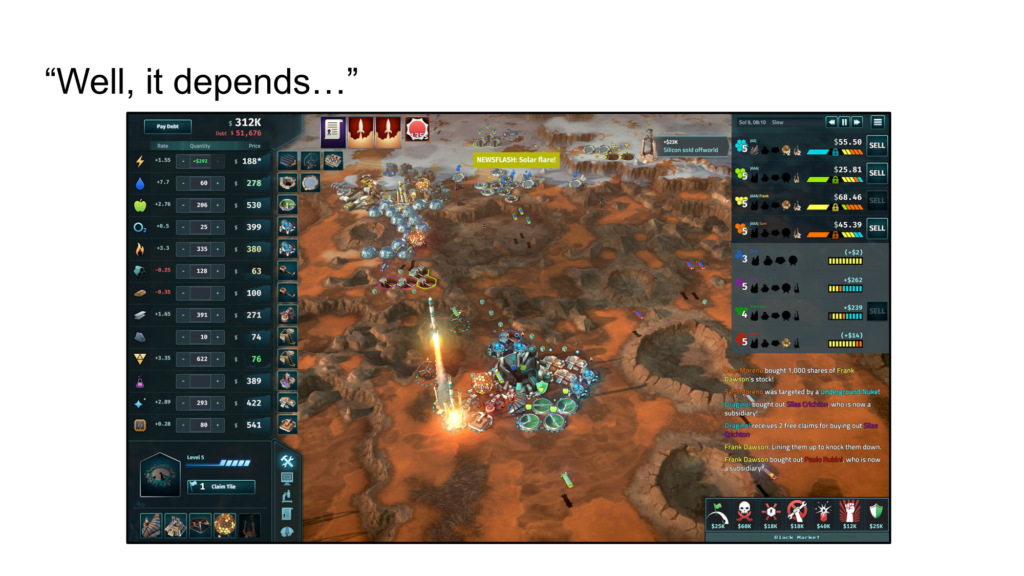

More broadly, I made Offworld for the same reason I made Civ 4, to push against dogmatic ideological thinking, the idea that there is one solution to everything. In a good strategy game, the answer to every question – which resource is most important? what should I research first? – must always begin with “Well, it depends…” The point of having to make tough choices and to adapt to the environment is that there is never, ever just one right approach to every situation. Ideologies inevitably lead to a belief that there is one set of solutions to the world’s problems, and I believe that a good strategy game always challenges this type of thinking.

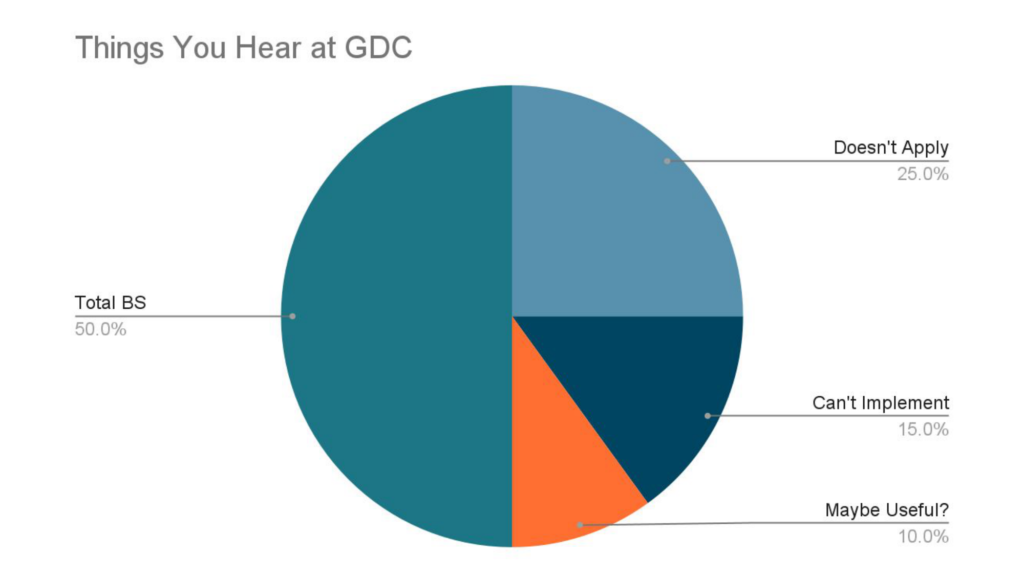

OK, now I am going to tell you something that is definitely in the 10% useful part of this pie chart. We game designers have no idea what we are doing. To be a good designer, you have to abandon the idea that you are anything other than an explorer.

You know how we all feel like we are impostors? Well, what if we are actually right? It’s actually bad to lose this feeling. If you think you have figured out game design, your career is over.

We are not creating ordered systems. We are creating chaos for the player to find order in.

I would extend this quote to say that designers who try to make ordered systems put their intentions, the meaning of their games, at risk because players will break those systems. Players don’t care about the imaginary game you have in your head.

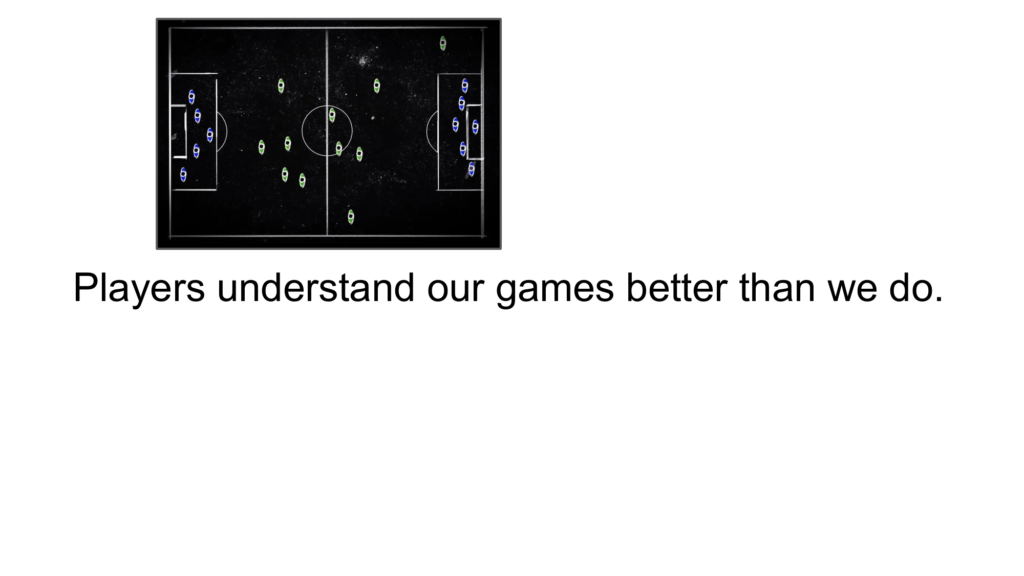

Indeed, player understand our games better than we do. When evaluating design talent, the most important trait I look for is humility. Designers need to be able to hold two contradictory ideas in their heads at all times – to hold true to their design vision even when success is uncertain BUT ALSO to always assume that their vision is meaningless until they see it the hands of real players. They need to have both a big enough ego to follow their own path but a small enough ego to assume that they are probably wrong.

So, why make games at all if the players ultimately take them away from us? Why am I still here, trying to climb up that hill?

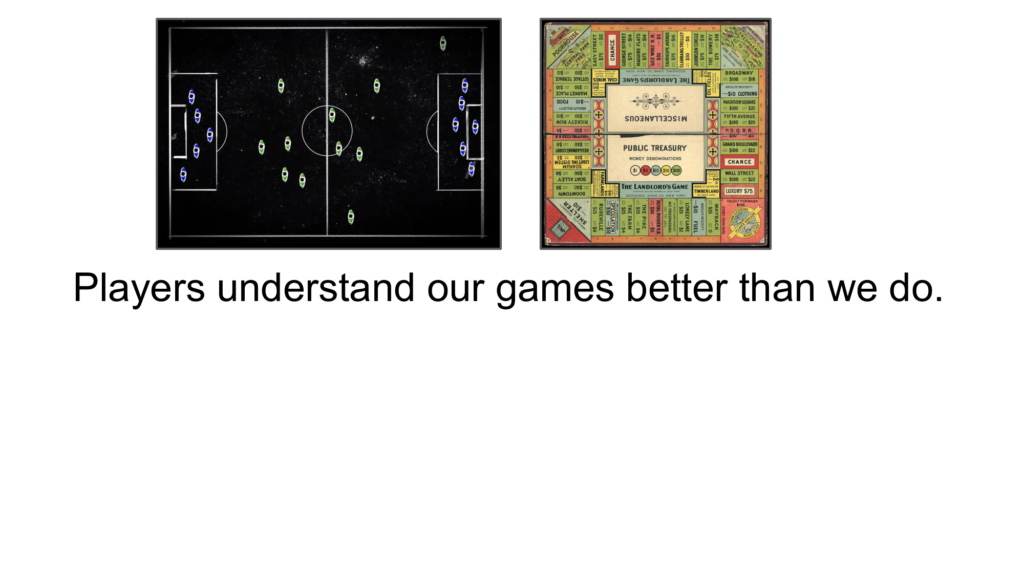

Well, what if that infamous Barbados-Grenada match was actually the most interesting game of soccer ever played? Maybe it’s amazing that a soccer team ended up defending both goals?

Maybe it’s amazing that the socialist Landlord’s Game turned into the capitalist Monopoly?

Maybe it’s amazing that Sweatshop created more empathy for sweatshop managers than for the suffering workers?

Maybe it’s even amazing that Spent somehow made people less sympathetic towards the poor.

Strictly speaking, these four examples are all failures, but the way they fail doesn’t at all suggest that games are useless.

Instead, their failures show us just how powerful games can be.

Right now, we are like children playing with fire, we don’t know what we are doing, and we might end up setting the wrong thing ablaze.

In the spirit of humility, I don’t have the answers for how to make sure our games don’t end up conveying a message that is the opposite of what we intended, but I do know of some games that have succeeded better than others, and I bet you do too.

Just remember that simply stating that your game is about X or Y doesn’t make it so. The only people who truly understand your game are your players, so if you want to know what your game means, make sure you ask them.

Thank you for your time.

Pingback: You Have No Idea How Hard It Is To Run A Sweatshop, Part 1 | DESIGNER NOTES